We first fell in love with your work when we saw your debut film, The Apology Line, at the Clermont Ferrand Short Film Festival and that was a good five or so years ago. You’ve since been on a roll – how would you say your work has changed since then?

I have definitely used the fantastic opportunities that have been afforded me to experiment and explore many different forms of filmmaking but mostly expanding my skills as a storyteller. I am still fascinated in exploring the human condition and reflecting current social issues through my work, so not much has changed there, but it is now about finding new and original ways to do this.

Rolling through your reel, it’s easy to be amused by many of your videos, particularly the feel good ones (more about these in a min) but the absolute stand-out piece is Benjamin Booker, The Future is Slow Coming. It’s raw and tragic and astoundingly shot and directed. How did this production differ for you?

Thank you for the kind words. This is one of the projects I am most proud of. It is so rare to be given the freedom and trust I was granted with this project and allowed to create something straight from the heart. The label gave me carte blanche and Benjamin gave me his complete trust, including letting me convince him he could pull off the performance required to anchor the film. No one wanted to hold back so that really gave me the space to tell the story I needed to tell. With everything that was going on around us this was one of those times I felt I had to say something as an artist. I was compelled to make a statement.

One of my most important projects of this year, a separate video for a different artist but in the same vein of socially aware narrative (a video about the issue of gun violence and lack of gun control in America), is frustratingly being repressed by the very band and management that initially commissioned it and encouraged us to make a bold statement. When it came to it they ended up being too scared to be associated with such a strong message and feared upsetting anyone. They won’t even release the footage to us. This constant fear of having an opinion or a socially aware message drives me insane. With the dawn of the age of Trump, now more than ever, we need to stand up and make ourselves heard.

What triggered the idea and were you involved in writing the narrative?

The story was actually based upon some of the themes and ideas I’ve been developing for a feature film combined with the message inherent in Benjamin’s powerful lyrics. I also felt a need to reflect the troubling stories we were witnessing of institutionalized racism and use of excessive violence in the police force. Protests against the police and the Black Lives Matter movement were also fascinating me and were something I wanted to touch upon. I pulled all these influences together and wrote a story set in the past but that was a very clear reflection of stories we were seeing today in the news. By setting it in the past I wanted to show how little we have progressed, like Benjamin stuck in a time-loop within the small town, we are stuck in a constant loop of repeating the mistakes of our past.

You’ve been collaborating with Mike Rosenberg of Passenger for several years now – we love your much earlier 27 and now this beauty, When We Were Young, which takes a completely different tack. In a time when music videos tend to focus on a younger audience your film encapsulates the happiness of an older generation in a non-cheesy, unpatronising way. What were your initial thoughts for the video and how did these evolve into the final narrative?

I often start with an initial thought from Mike which I then take and evolve into a video concept. Mike usually has a simple visual that has always been in his head for the song so it is about expanding upon that and giving it meaning. For When We Were Young we wanted to show a group of friends hanging out, laughing, joking, reminiscing and dancing down the pub. Just like we all do. But on this occasion they happen to be older and with a long lifetime of experiences and memories. I wanted to go on a simple emotional journey with these characters, to live in their skin for a short while.

How does the filmmaking process work with Mike Rosenberg?

I’ll feed back my ideas and elaborations on Mike’s initial thoughts and we’ll build it from there. We have developed a lot of trust with each other and that goes a long way to keeping the process smooth and focused. For the videos on this last album they got in touch and said they wanted to do all three videos in one go. So we found ourselves shooting two videos in Iceland over a week and then this one back in London the following week.

It’s beautifully shot, lit and paced perfectly for the track. What were the challenges of the production and how did you go about resolving them?

This was a wonderfully calm shoot. I always try and ensure my sets are relaxed and the shoot is enjoyable, we are so lucky to do what we do that it should be a fun experience, even when we need to get serious or emotional. I find that by creating this kind of environment everyone pulls round and gives you their all, they actually want to give that extra 10%.

My cinematographer for this project Ben Moulden did a frankly outstanding job of lensing this video. I said I wanted to imagine we were shooting the whole thing on a vintage medium format camera and almost treat it like a photographic portrait series. Alongside the cinematography it was all about the casting and creating a relaxed and fun environment for my cast to feel comfortable and act naturally. The key is to know when to interject with direction and when to sit back and let reality unfold.

The edit was by another director whose work I’m a huge fan of and really admire, Daniel Henry. His own directorial work shows you what a master of pacing he is and I was very fortunate to be able to call on him for this.

Where did you shoot the film?

We shot in the legendary George Tavern on Commercial Road. Like everywhere with any history and soul in London it is under threat from money grabbing developers. If you haven’t already, please sign the petition to help them fight for their survival. We need to keep these places open and functioning as their original purpose. https://savethegeorgetavern.com/

Some of your work is very literal, although told with your distinctive eye. For instance, your film Molly for Lil Dicky picks up on the minutiae of the lyrics but has that wonderful twist. How did that narrative evolve?

For Molly I worked very closely with Dave (Lil Dicky) to construct the narrative. Dave came to me with the basis of the concept and I went away and wrote the story and how it would unfold. I really enjoy an artist who is looking for and open to engaging in a collaborative creative process, you can achieve so much more as you are essentially working to create a visual accompaniment to their original material in the first place. Dave had the idea of the twist, so I give him full credit for that. But I had to figure out how to pull it off effectively and keep the audience fooled until that moment. For me it was all about keeping the whole thing feeling very real and very relatable for everyone watching. We’ve all sat at that table at the wedding. Or had that feeling of watching someone we once thought we had a future with go on to have a future with someone else.

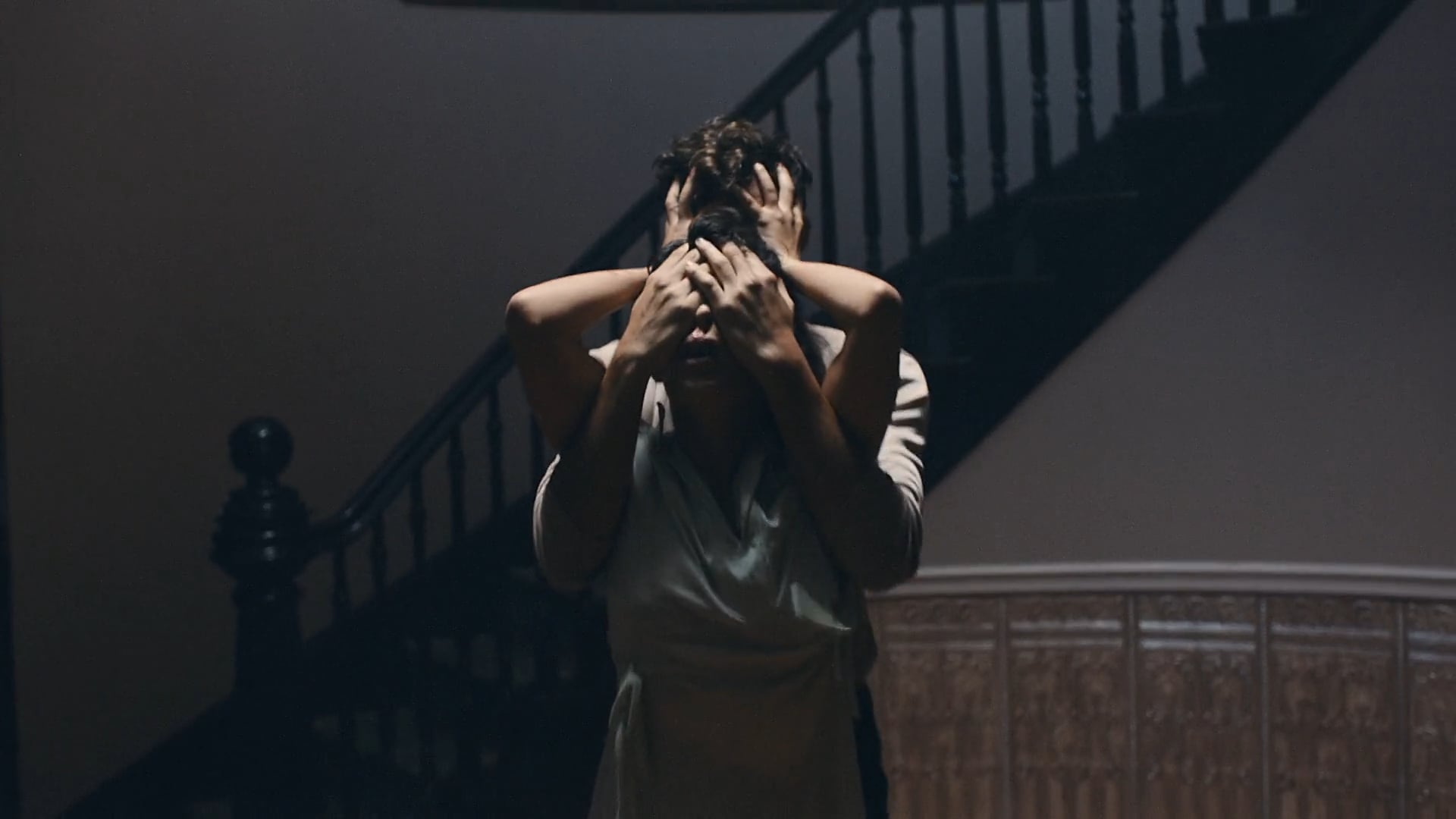

What were the main challenges of directing your choreographed film, First World Problem for Unknown Mortal Orchestra and how did you resolve them?

UMO’s video was a step in a very new and exciting direction for me. My co-director, choreographer and dancer Kiani Del Valle is such an original and unique voice in dance and we had been mutual fans of each other’s work and wanting to work together for a while. It has been fascinating for me to experiment with telling narratives through dance and movement but definitely a challenge to think about storytelling in this different way. How were we going to tell this emotional journey of our lead? How were we going to bridge the two worlds we wanted this ‘relationship’ to exist across without breaking the flow of movement?

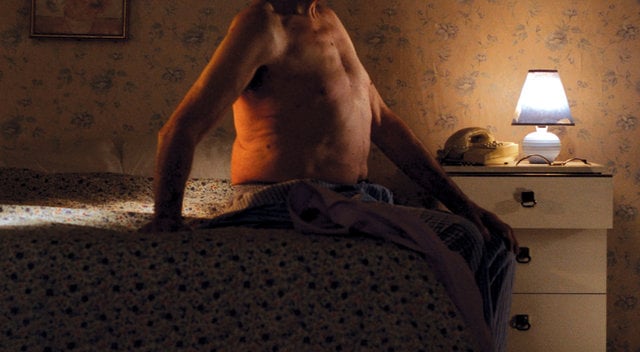

You’re not afraid to point the camera in places where many might shy away from – in particular your Define Beauty series for Nowness. Were you given a detailed brief for these pieces or were they entirely your own creative responses?

Nowness gave me a subject matter, mostly just a single word and then some pointers to what they were hoping to achieve with the series and then just let me come up with my own ideas and run with them. They have always been immensely trusting and consistently looking to provoke debate through the films so it has been a very fulfilling collaborative process. For Heavyweight I wanted to turn a spotlight on what our society and the media deems sexy and force us to reevaluate our preconceived perceptions. For Cooked (Degrees of Doneness) I wanted to do something completely different and have fun with it, simultaneously highlighting the damaging aging affects of tanning and the rather grotesque concept of cooking ourselves like we cook meat.

Do you have any personal projects currently on the go?

I have a few projects I am very excited about. It’s funny you mentioned The Apology Line as we are currently looking at reviving the art project in different countries and collaborating with some very exciting new artists to expand the project on many fronts, not just through film.

I am also developing a couple of feature film ideas, one of which revolves around a young black musician trying to find his place in life amidst racial tension, economical woes and fervent spiritual beliefs of the Mississippi Delta of the 1920s. It heavily incorporates a lot of the early blues music of which I’m currently a little obsessed with.

You’ve divided your time between LA and Europe. Are they completely different worlds to live and work in? Where do you call home now?

I don’t think they are too vastly different, although after this week’s election we’ll see if that holds true! I find LA very inspiring in terms of its film community and optimism, something London can sometimes lack a little. But I also find London hugely inspiring for it’s more daring and leftfield creative. So straddling both worlds is hugely beneficial and I feel very fortunate to be able to do that. As an adult I have moved around quite a lot so home is wherever I’m laying my head that night.

LINKS