Martin Stirling has created and directed four charity films over the past year which are all shocking, disturbing and very effective – Lego has ended its partnership with Shell, the Pentagon issued a statement on force-feeding (although sadly hasn’t closed Guantanamo Bay) and his films for the Syria campaign are embedded in our psyche. The emotional nature of charity scripts of course makes for compelling viewing, but it’s Stirling’s cleverly crafted film-making which has made these ads really stand out.

How did your involvement with these charity ads come about?

I was at the agency Don’t Panic having a meeting about something completely different when two women burst into the room saying ‘Mos Def wants to do something on Guantanamo but he’s only here until tomorrow, what can we do?’

They were from a legal charity called Reprieve who had recently got their hands on a Guantanamo handbook entitled ‘Standard Operating Procedure for Force Feeding’ – it’s meant to be a medical manual but it reads like a military handbook. I blurted out ‘Why don’t you just use that as a script and force feed him?’ and that’s where it all started. It was one of those rare serendipitous moments where I just happened to be in the room at the right time. I was probably pitching out of turn but it’s not everyday Mos Def rocks up.

What happened next?

I called up my boys and said “So…we’re going to force-feed Mos Def. There’s no money and it’s got to happen tomorrow. You in?” and within an hour the crew and studio were in place. It all happened so fast because Yasiin was only in the UK for such a short period of time. David Morrissey was producing the ad – that’s right, the bloody Governor from The Walking Dead! – he asked if we minded Asif Kapadia directing to create more buzz. I didn’t mind, I knew it would get the piece to a wider audience and Asif is a brilliant director and a great guy so I ended up creative directing the project.

What did you learn on this film?

We’d set out to get in Obama’s face, or at least put pressure on him – ten hours after the film went online the Pentagon had to release a statement about the film. It did the job. It made me realise the power of storytelling online, that it’s possible to have an immediate effect and watch that unfold.

You followed this with one of the biggest viral videos of the year with the Most Shocking Second A Day video. How did that come about?

The agency came back to me with the idea of using the one-second format to create a film about the conflict in Syria. I thought it was perfect for a YouTube audience. It speaks the same language as the platform it’s designed for, it uses the same grammar as the audience. More importantly it’s a unique narrative device which pushes the story along like a runaway train, it’s overwhelming, relentless, unforgiving (much like Syria). It puts the audience in the little girl’s shoes, the confusion, a fragmented distortion of reality, the futility of trying to hold onto a moment creates this feeling of helplessness.

How did you prepare for the shoot and how much time did you have from greenlight to delivery?

I watched Threads, the BBC series from the 80s, which cleverly leaks the story from the background elements, radio reports, TV news items, that sort of stuff. I loved how incidental and subtle it is, the sense of impending doom creeps in slowly to the foreground until everything is a big fucking disaster. We thought that would be the best way to tell our story too. The script was written by myself and Don’t Panic, we read dozens of case studies from refugees and survivors in Syria and started to feed those into the storyline.

Again in terms of delivery, it all happened very quickly. From greenlight to delivery it was about two weeks of solid working around 16-hours each day. We had two days to shoot 80 different scenes, each scene was a location change and we were working with kids so we couldn’t run over. Everything had to be timed to the minute. We spent days and days scouting to find the right locations that were concentrated enough to save us those precious minutes. Luckily we had a militant 1st AD, she was bang on with the schedule and we actually ended up wrapping five minutes early on both days.

What was the atmosphere on set like, is it different for a charity film like this?

I like to keep the tone on my sets light and fun, I want my set to run off laughter even if we are making something as serious as this. That’s just on the surface though. There is something underlying on charity shoots, the client is someone everyone is behind, there is a feeling that you don’t normally get when you are shooting a straight commercial. It’s more implicit, that people are being driven by a slightly different engine. There’s a stronger sense of responsibility that what you’re making could have a genuine impact on people’s lives so you’ve got to get it right.

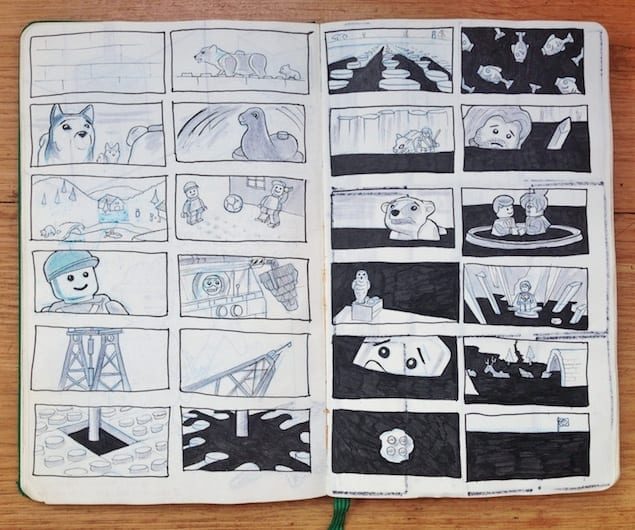

Do you normally storyboard everything beforehand?

Sometimes I storyboard and sometimes I don’t. For this I storyboarded every scene. Normally you have a character in a blurry background but for this it was the opposite – the girl was like a silhouette in the foreground of each panel, the detail was in the background which is where the story is really unfolding.

Where did you find the girl?

We went to quite a few casting directors who specialise in children and because of time restrictions we didn’t do in-the-room casting, which I love to do, we just watched tapes of kids in rehearsals and we found Lily who was incredible. She had so much energy and lightness to her we knew she would make it through the challenging shoot without losing focus. A lot of the success of it is based on her performance. She nailed it.

Her performance feels genuine and realistic – not hammy at all. How did you direct her on that?

I’ve got a pretty good cheese detector. I’ll beat any of that out with my fromage stick!

Seriously, it’s about knowing your actors. What makes them tick. As a director I’m not there to tell them how to do the performance. I just have to be sensitive enough to set the right conditions on set so they can work their magic.

I like to work in many different ways but improvising seems to work well with kids. If you tell them particular lines or tell them to say these words – even adult actors suffer from this – they become self conscious of saying lines in an exact way, whereas if you create an environment where they feel free to say or do whatever they want you’ll get the most natural reaction. So with Lily we did a lot of improvising and said “this is what is going to happen in the scene, just do whatever you feel is right”.

One of the big moments that always gives me the chills when I watch it is when she is running down the stairs and says to her parents “What’s going on?” and you can sense a real genuine fear in her voice. That line wasn’t scripted. It captures that fear you get when you first see your parents cry, your world falls apart – she got into that moment and that’s what makes it.

For me it always comes back to the viewer. Audiences are so discerning, the moment something feels even slightly inauthentic you lose them. One tiny crack in a performance and it’s game over. That’s why the second art of acting is so important, the edit.

You seem to place a lot of emphasis on the craft of filmmaking, what do you feel is the most important aspect of filmmaking?

I think there is a common misconception that film is a visual medium. This is going to sound really wanky but it is above anything else an emotional medium. It’s the closest thing we get to dreaming which isn’t just about pictures, it’s a weird experience of shifting space and time and emotions which contort and change in an instance. I started off as a fine artist so I naturally gravitate towards the image, but as a director I’m conscious that I’m crafting an experience not a succession of pretty pictures.

What have you learnt from your short time working in advertising?

The thing I love about advertising is that it forces you to be simple, it has to be simple to be effective. You have to have one idea and it’s very easy to try and cram too many things in. That’s something I suffered from early on. You have to trust that you can tell complex stories in a very short period of time through simplicity.

I watched a short film called Dog by stop-motion animator Suzie Templeton – it was her RCA grad film which won a BAFTA. I was so upset, absolutely heartbroken after watching it and I thought how on earth did you do that in only three minutes? Up until then all of my films had been about ten minutes long and they didn’t really pack much of a punch, they were quite forgettable. I realised then the power of brevity, to keep things simple and to find a way to connect with the audience – people go away remembering how they felt, not what they saw.

So LEGO?

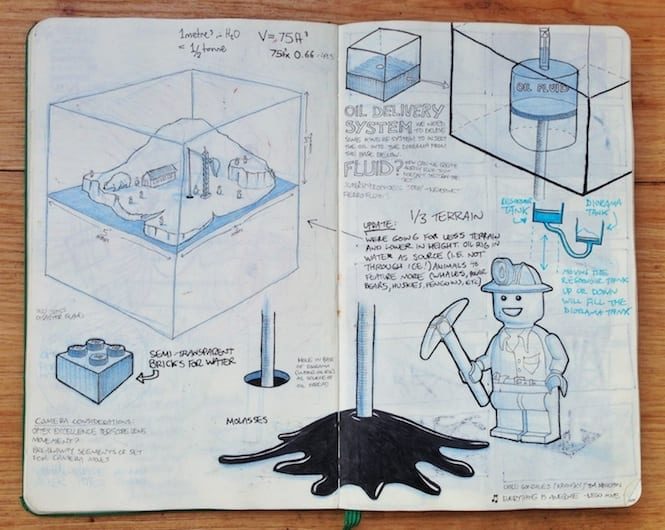

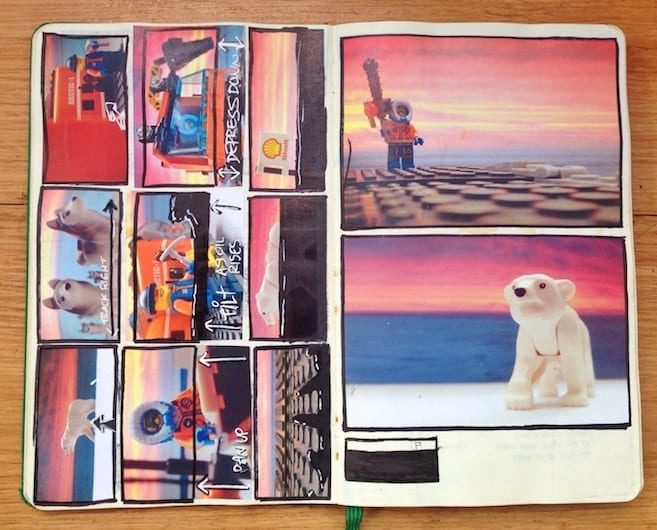

Don’t Panic came to me again with a morsel of an idea. A great idea. They wanted to drown an Arctic diorama in oil. I saw it in my head immediately, I could see the faces, the viscous oil curling over the nodules of the Lego. It was sufficiently naughty so I said I’d do it!

Where did you start?

I’d built up a huge amount of trust with the agency by now so they were super awesome and just let me and the crew get on with it. That’s a great feeling when people trust you enough to leave you on your own. Anyway, the concept was there but I wanted to find a way to capture a feeling of lost innocence due to this relationship between Lego and Shell. I knew it’d have to connect with the audience on an emotional level – with little bits of plastic it was going to be a challenge. But I love challenges. I rounded up my crew and said we’ve got to make this thing within two weeks, how do we do it? And two weeks later we handed it over.

How did you go about creating the set?

Initially I conceived it as an art piece which after filming could perhaps be placed in a gallery. I designed it as a tank which would fill up with oil and disappear again and reveal a pristine Arctic landscape. It would be on a cycle where the oil would rise up and there would be a giant black box in the middle of the gallery space and it would disappear again. We costed it up and it was very expensive to do because of the tons and tons of liquid metric pressure, so we realised we were going to have to be crafty and build it purely for camera. That involved multiple pieces and magic lenses to make the set feel bigger than it really was. We had a tight budget so we begged and borrowed LEGO from friends, family and freecycle centres. In the end we used about 160kg of LEGO and 50 gallons of ‘oil’.

When did the music come into this?

I watched the LEGO movie and the song ,Everything is Awesome’ is so kitschy and annoying, it just seemed like the perfect song to go over this beautiful destruction. By shifting the tone of the piece but keeping the same lyrics felt like a super subversive way of conveying the message. The music was composed by the super awesome Alex Baranowski who used singer songwriter Sophie Blackburn to record the vocals. They both nailed it. It was perfect, they captured exactly the right tone.

The video immediately went viral, there seems to be a pattern emerging do you have a winning formula?

There is no formula or way of detecting what will and won’t go viral. It’s completely out of your hands as a creator. I just focus on telling a beautiful and moving story that hopefully people will naturally want to share. Obviously there are ways of increasing your chances though. You have to have a strategy too but the content has to hold up first. There’s so much shit online competing for people’s attention you have to be wise to that and try and create a fuss in new ways.

Don’t Panic are really good at knowing what are the key triggers for people to share on YouTube…like there are nods to Game of Thrones, Harry Potter, Halo, we even built an insane Fortress of Solitude from the Superman films out of LEGO but we were running out of time and we couldn’t shoot everything. It was a tough decision to leave that out but this wasn’t meant to be a pop culture checklist, we still had to tell a story. I want people to go “oh my god they’re drowning my childhood, not oh that superman set looked amazing”.

So tell me how your latest film for Syria ‘In Reverse’ came about?

I received an email from the client – a coalition of charities – who wanted to make a film raising the awareness about Syria for a UN convention. They were fans of my previous work and decided to contact me directly to see if I was interested. They had a strict deadline because apparently global leaders won’t move their meetings for some smalltime filmmakers so again we only had two weeks to deliver.

I was very interested but the issue was that I had three other jobs on and one of the films was the Philips commercial which involved a lot of preparation, I couldn’t possibly take on another project. It looked impossible. But as a tried to walk away I was haunted by the images and stories I’d encountered on the first Syria film.

They were so horrifying I got completely sidelined. I realised I didn’t want to do this for me or the idea or just to make a cool film anymore, it was about making this because it actually might help someone. I felt a responsibility as a filmmaker, I couldn’t justify making something for money over doing this so I dropped one project and decided I could deal with three hours sleep a night for two weeks.

So I foolishly said yes, wrote the script, reversed it, storyboarded the idea and said if you’re ok with that we have to shoot in the next two days as it was the only time we could get away from the other jobs. The client trusted us and said go for it.

That afternoon we booked flights to this tiny town near the Turkish-Syrian border, we wanted it to look authentic, and literally landed, went straight to a street casting in this village and did a location recce, had a quick rehearsal, went to bed, shot it the next day, and flew out again that night. We had to shoot so quickly because of the visual affects work that needed to be done which was an insane task, but Cherry Cherry did amazing work. They had 10 days to do everything. Unbelievable.

Everyone was at capacity on this job but we ploughed through, it just became a unanimous decision by everyone, that it was for a really good cause and that you can get over fatigue, but people don’t get over their lives being shortened and that’s what this film was trying to prevent.

So you were working on the Philips commercial concurrently?

Yes Philips was gearing up and for the main film, the 90-second version, we were looking at doing purely stop motion with humans and sets and a change every two frames, with over 500 prop changes – sofas and chairs, and walls and doors and curtains and you have to line everything up and we had two days to shoot that.

We got back from Turkey and went directly to the pre-light for Philips and then we shot for the next two days, and edited both concurrently. It was slightly insane and there were a few 40 hour days just to get them both done. They both had the same delivery date but luckily Alex Burt who edits most of my work is a bloody machine and powered through like a trooper. Feed that man tea and he’ll go for days.

What did you shoot Philips on?

We ended up shooting on a Red Epic (Dragon chipped) because we had live action moments as well – it was purely because we would have lost too much time switching the camera head to a stills. That was quite a militant shoot as well: a prop goes in, we’d turn over, capture that very quickly, get it out, change the next prop and choreograph the actors. We had two minutes for each shot and had to keep that rate going for two days. We had to shoot chronologically moving through the ages, so any deviation from that plan would have brought the whole thing crumbling down. It was shot in 5K as well, the size and file of data was just monstrous, huge. Completely impractical.

The production design is incredible, how did you manage that?

Two words. Sarah Jennesen. It was the first time I’d worked with her, but she designed the shit out of it and brought the most stellar team with her. We were telling a story through the set and props so finding the right collaborator was key. I spoke to a lot of people about doing this job and you could just see the fear in their eyes – it was a Himalayan task not only on set and to turn it around in time but the amount of props and finding them, it was gargantuan and she embraced it. Maybe she’s a masochist or something but I know we couldn’t have done it without her and her crew.

What’s next for you?

I’m shooting my debut feature in Detroit at the beginning of next year. And I can’t bloody wait!