What triggered the narrative and how did it evolve?

The seed for Marriage Unplugged was planted long before the script assignment that eventually brought it to life. Back in 2017, we attended the Media Future Day, where we heard Trudy Barber, an English professor, give a fascinating talk about the history of computerised sex toys. That was the first time we seriously started thinking about the intersection of intimacy and technology and how it might one day translate into a film.

Years later, during Kim’s Master’s in Screenwriting at the London Film School, there was an assignment to write a script set in an interesting location. Combining our long-standing fascination with sex robots and a more recent visit to a sex shop, we decided to set our story in a sex robot shop. From there, the story developed quite naturally: a couple buys a sex robot to fix their marriage, only to find that the robot becomes the catalyst exposing the cracks in their relationship.

We were drawn to the absurdity of the premise, but also to its emotional core. We wanted to use humour as a way in, and then gradually strip away the layers until what’s left is something raw and painfully human – a story about loneliness, longing, and miscommunication.

What was your creative process for writing and prepping the production?

The first draft was written very quickly – actually in the course of a single day by Kim. But from there, we went through many months of rewriting and reshaping together, making significant changes along the way.

A big part of our prep is always visual world-building. We developed a detailed colour palette early on, which became the foundation for the film’s atmosphere. Once we had that visual identity, we briefed all our heads of department to ensure a cohesive tone across cinematography, production design, and costume.

Location scouting was another major step. We looked at over ten different houses before finding the right one that captured the emotional emptiness of the couple’s home. Finally, casting and rehearsals were crucial. Working with Nikki Amuka-Bird and Nicholas Gleaves, we dug deep into the backstory of the characters – exploring their shared history so that when they performed, there was a lived-in authenticity between them.

Tell us more about the development of the robot?

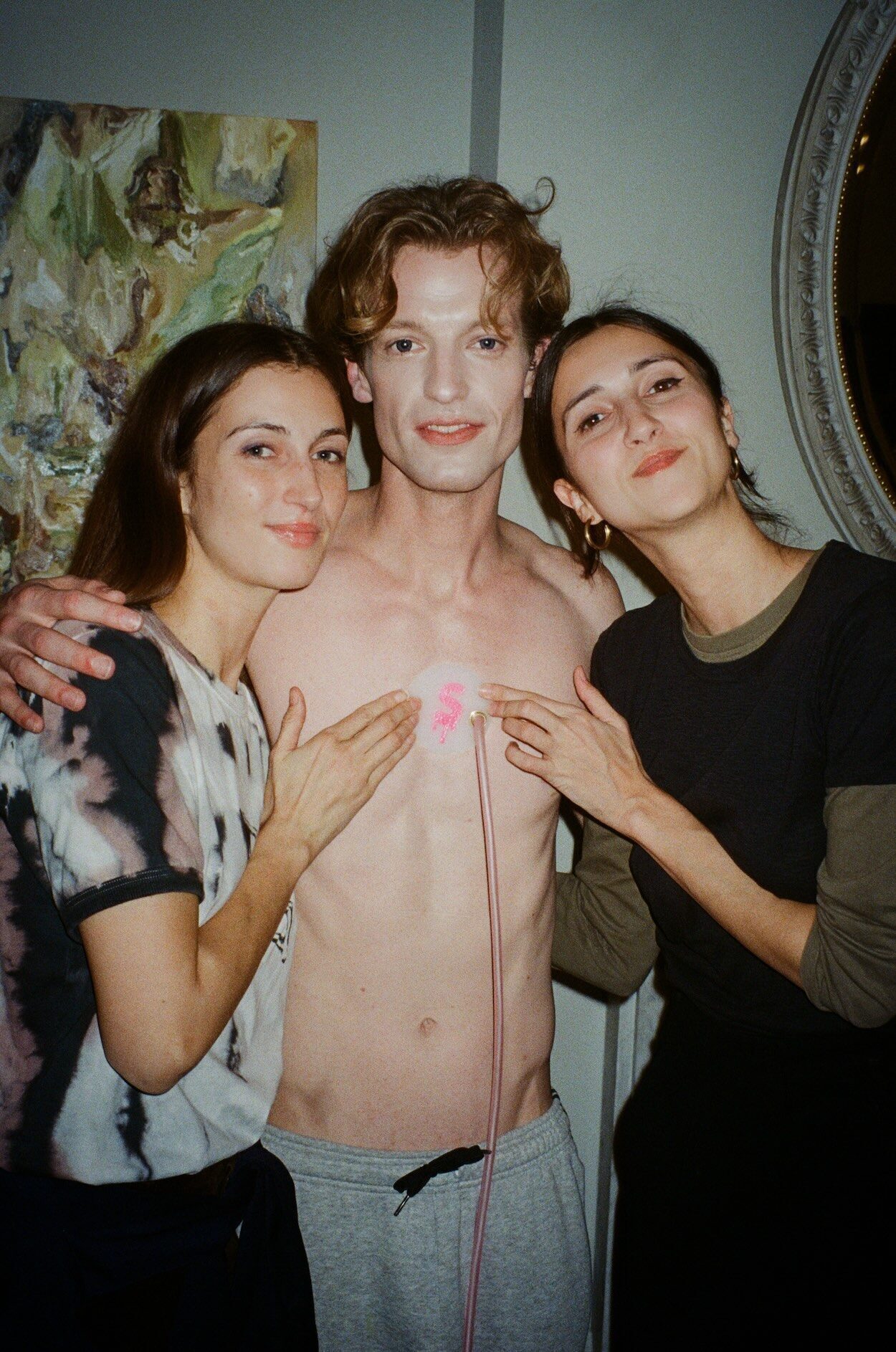

The design and casting of the robot was one of the most important parts of the film. The robot wasn’t meant to have desires of his own, but to mirror those projected onto him, becoming almost two different characters – one for the husband and one for the wife. So the robot needed to function both as a sex object and as something childlike, which is a difficult thing to embody. Casting was key and we saw many talented actors – by the way of our great casting director Catriona Dickie – before we found Sven Ironside. He captured all the nuances of the character beautifully in his performance, finding the delicate balance between the mechanical and the human, and shifting his energy depending on which character he was reflecting.

Beyond performance, the creation of James was a collaboration across departments. Visually, we wanted him to look almost human, with only subtle hints of artificiality – the perfection of his skin and the slightly uncanny quality of his eyes. We have to thank our make-up artist Dasha Taivas for the great look. In post, our sound designer, Kaspar Broyd, gave James an extra layer of oddness and machine-likeness through subtle sound textures that hint at his artificial nature without ever making him feel robotic in a conventional sense. The result, we hope, is a character who feels real enough, but also lightly unsettling.

Working as a duo do you have separate roles or do you both direct in sync with each other.

We truly direct in sync. If we had to define a division of labour, Flo tends to work a bit closer with the cinematographer, while Kim spends slightly more time with the actors. But that’s not a strict rule at all – we both take on all aspects of directing.

We’re very much in tune creatively, sometimes even calling “cut” at the exact same time, which always makes the crew laugh. Being sisters probably helps – there’s an unspoken understanding of each other’s instincts, and we often know what the other is thinking without needing to say it.

How do you reach the “right” decision?

Because there are two of us, there’s naturally a lot of discussion involved, but we rarely disagree for long. We talk things through until we reach a solution that feels right to both of us. Most of the time, our instincts align quite intuitively – perhaps one of the perks of growing up together.

Importantly, most big decisions are made during pre-production. We like to arrive on set with a very clear plan and often pre-empt possible problems by preparing multiple solutions. That preparation means that once we’re shooting, we almost never have disagreements – everything flows quite naturally.

Were there any particular challenges with the shoot and production?

Time was our biggest challenge. Like many low-budget projects, we were working to a very tight schedule and ended up shooting the entire short in three days. That meant making some tough choices – we had to cut two scenes, for example.

The sex robot shop scene was especially tricky. We only had access to the space on the shooting day itself, and it required a complex set build. We were running behind schedule, but our incredible crew jumped in to help build and dress the set. Thanks to everyone’s effort, we still managed to capture everything we needed – it was one of those moments that reminded us just how collaborative filmmaking truly is.

Was your childhood particularly creative and where were you brought up? Where are you two based now?

We grew up in St. Gallen, Switzerland, in a very creative household. Our mother was a teacher who also painted and wrote, and our father was an architect who loved technology. Between them, they gave us both artistic curiosity and a fascination with how things work.

Our mother encouraged storytelling – she’d role-play with us and help us invent characters and worlds. Our father always had the latest camera gear and constantly filmed family holidays and regular life. We later used those cameras to shoot our first short films when we were just seven and nine. We were also surrounded by cinema. Our parents had a huge VHS library, and we’d watch films on repeat until we wore the tapes out.

Now, Flo lives in Zurich and Kim in London, but we talk on the phone for around eight hours a day. It’s basically like we’re still in the same room – just separated by a few hundred kilometres and some dodgy Wi-Fi connections.