Bianca, you’ve said FaceTweak came together fast, almost spontaneously, yet it lands with such precision. Do you think that urgency, the rush of it, helped you access a rawness that a longer process might’ve dulled?

Definitely. I really love creating on instinct — there’s something creatively freeing about having to move fast and make quick decisions without overthinking. I actually believe a lack of time and resources can lead to more interesting ideas sometimes. Of course, it’s amazing to have access to all the shiny tools and endless prep time, but there’s a kind of rawness that can only come from working within constraints. That urgency forces you to trust your gut, and sometimes the most honest moments — in performance, tone, or visuals — come from that pressure.

The satire in FaceTweak is sharp, but there’s also a pain underneath it. A kind of quiet sadness about never feeling “enough.” Was that emotional undercurrent there from the start? Or did it reveal itself through the character as the film took shape?

That emotional undercurrent was there from the very beginning. From the conception of FaceTweak, I knew I wanted to explore that quiet ache of never feeling “enough.” The challenge was striking the right tonal balance — weaving in humor, but in a way that felt grounded in truth, almost a dark comedy rooted in the absurdity of real life. I never want to tell an audience how to feel, but I do want to hold up a mirror to something so many of us experience — regardless of gender or age. That lingering question: Am I enough? Am I lovable enough, successful enough, perfect enough — and who even decides what that looks like? I’m really fascinated by our relationship with perfection, how it shapes us, and how we chase something that might not even be real.

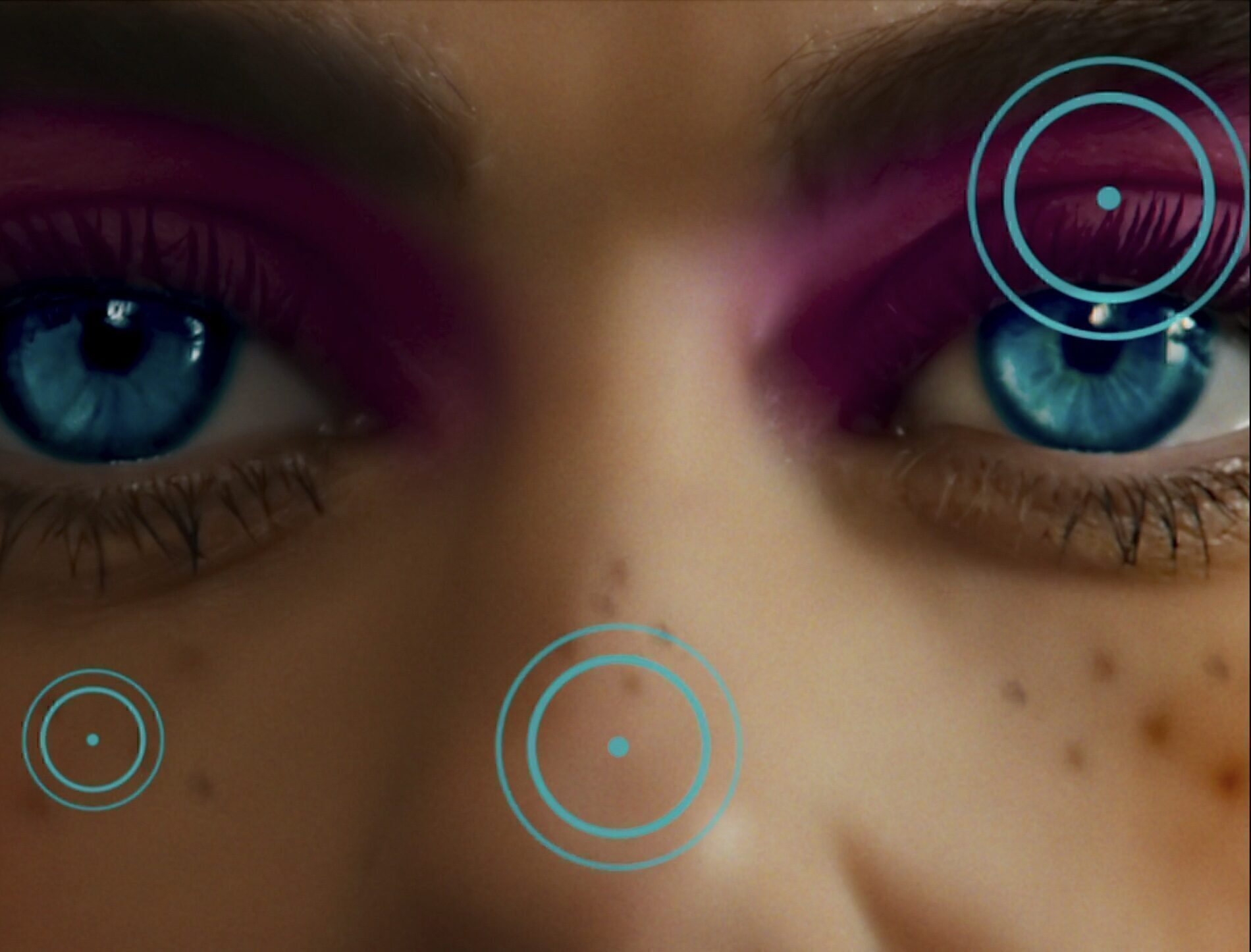

The protagonist’s obsession creeps in subtly, until it’s all-consuming. It reminded me of how easily self-image becomes distorted when we’re exposed to constant digital “improvement.” What were you aiming to capture in that shift, and how did you want the audience to feel as they watched her lose her grip on what’s real?

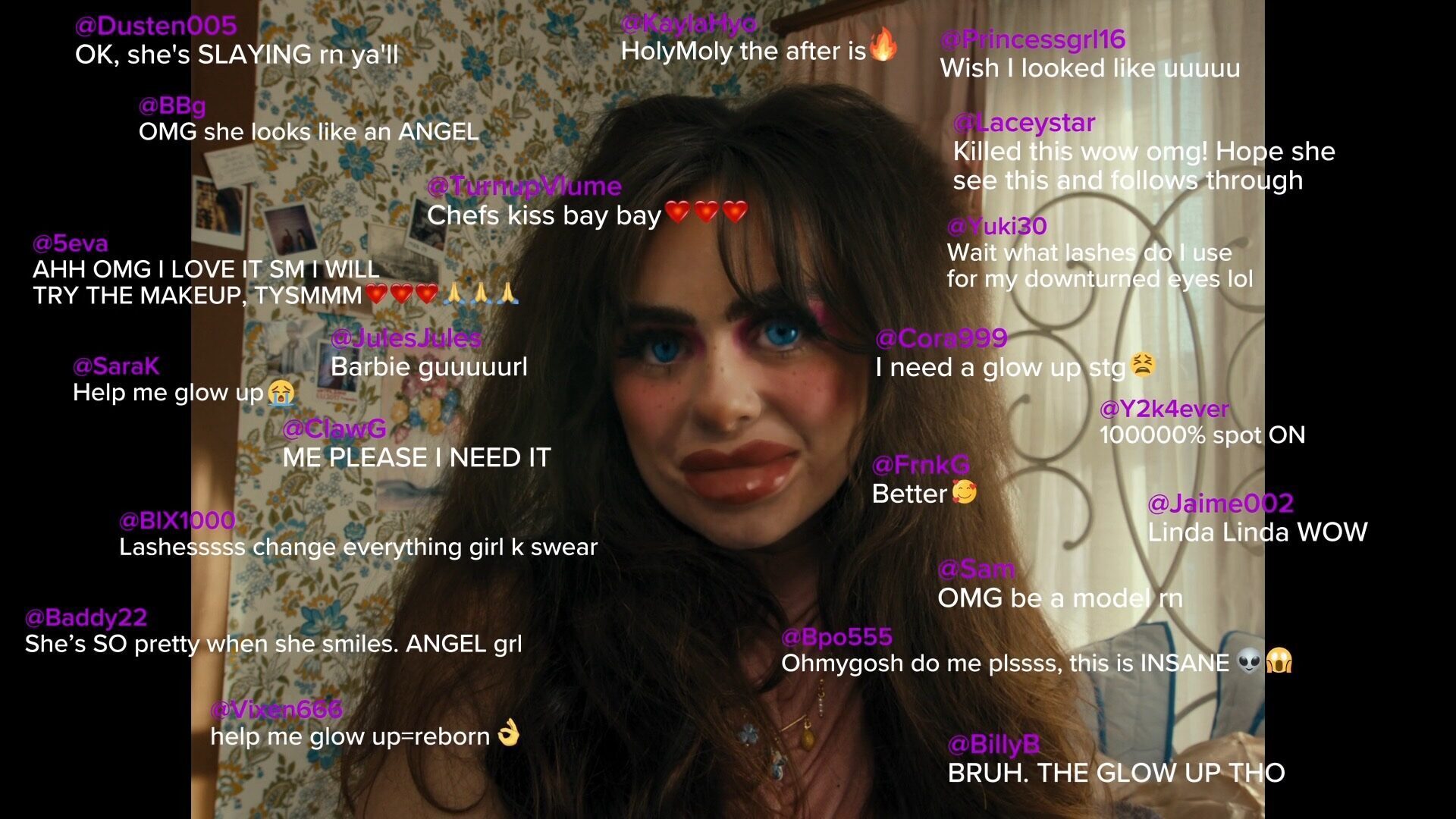

Love that — yes, that was exactly the intention. I wanted it to mirror the experience of doom scrolling alone, when you tell yourself you’re just going to glance at a few images — and suddenly, an hour has passed. You’ve absorbed hundreds of curated, “perfect” faces, bodies, and lives, and without even realizing it, your perception of yourself starts to shift. That’s what I hoped to capture — how subtle and insidious that transformation can be, but also how overwhelming and claustrophobic it starts to feel. I wanted the audience to feel that quiet unraveling, the way digital perfection can chip away at reality, self-worth, and our grasp on what’s actually true..

There’s a moment in FaceTweak when the bedroom – usually a private, personal space – feels completely overtaken by curated filters. While the film remains observational, were you interested in exploring how digital culture can seep into even our most intimate spaces? What did you hope audiences might sit with in that shift?

Yes, exactly. I’m really fascinated by how quickly our phones — even just a few seconds of scrolling — can completely infiltrate our mental and physical space. It’s not just when we’re holding the device; it lingers. It follows us into quiet moments — while we’re standing in line, sitting in traffic, trying to fall asleep — replaying images, comments, or comparisons that somehow embed themselves into our thoughts. With FaceTweak, I wanted to explore how digital culture doesn’t just live on our screens — it seeps into our most intimate spaces, even the ones meant to be safe and personal, like a bedroom. I hope it encourages people to reflect on how much space we allow these curated realities to take up — and what that might be replacing in the stillness of being alone with ourselves.

Your films, from FaceTweak to Video Barn and beyond, often explore young women navigating surreal, dreamlike worlds that feel emotionally complex. What is it about these perspectives and characters that draws you in? Why do you keep returning to these stories, and how do they reflect your own creative or personal journey?

I’m really drawn to the complexity of the human experience — especially through a female lens. We’re constantly evolving. A single decision, a fleeting moment, a relationship — these things can shift our path entirely, shaping new versions of ourselves over time. That emotional layering, that inner chaos and reinvention — I find it endlessly fascinating. I’ve always been curious about why we do what we do, why we’re drawn to certain people, or why we cling to specific habits or ideas. The human psyche, with all its contradictions, is just so rich to explore. I’m especially pulled toward characters who are a little messy, a little lost, but trying. I love stories where people are unapologetically themselves, even when they don’t have it all figured out. One of my favorite films is The Worst Person in the World — it captures that kind of raw, imperfect beauty so well.

You’ve clearly built strong visual signatures across your work with hyper-real production design, and emotionally layered characters. But there’s also a consistent thread of exploring girlhood and femininity in unexpected, often subversive ways. With Video Barn, you spoke about wanting to play with femininity in a cool, non-traditional light. Where do you see FaceTweak sitting within that ongoing exploration?

Thank you, that’s really kind of you to say. FaceTweak definitely exists within that same world — it continues my exploration of girlhood and femininity, but through the lens of beauty standards and self-image in the digital age. I wanted to challenge the idea of what we’ve been taught to consider “beautiful,” and more importantly, what we’re told is “enough.” I think that’s a question many women wrestle with throughout their lives. With this film, I hoped to push back against some of the normalized pressures placed on young girls and women, and explore the quiet, often internal toll of constantly trying to meet those impossible standards.