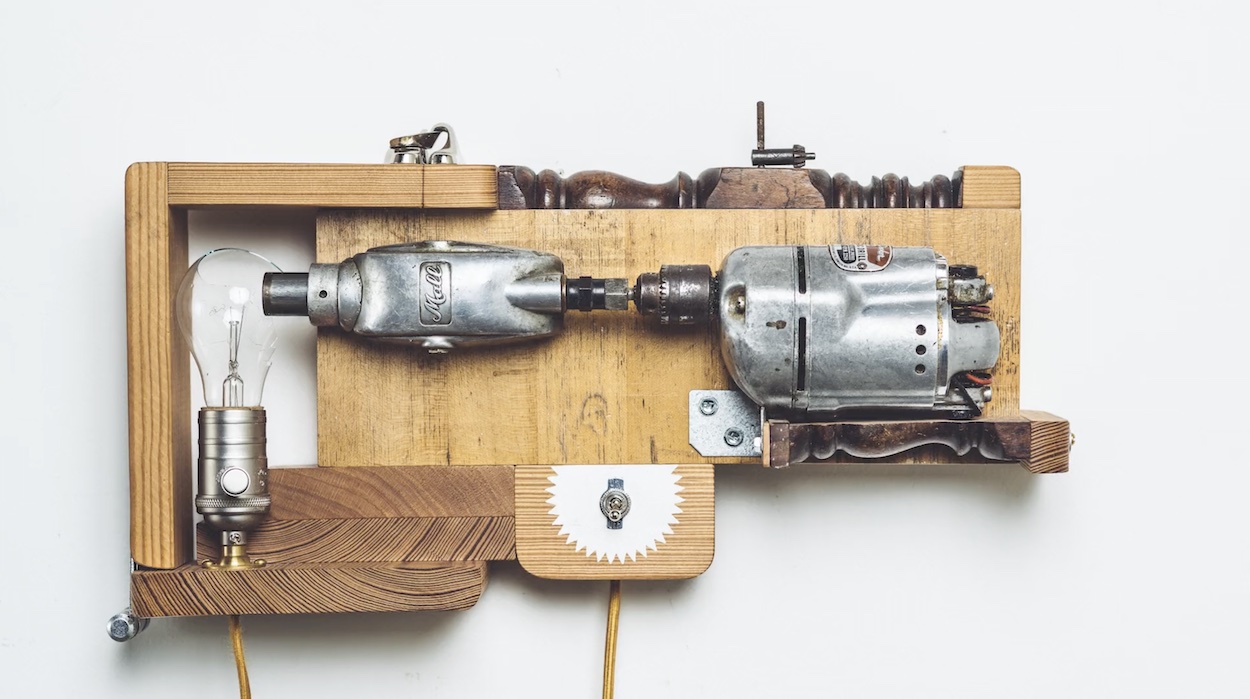

All photos taken from Mac Premo’s 1.4 gold winning film I’m Usually Good At Naming Things

As a multidisciplinary creative and craftsperson, you’ve worked in film, sculpture, art, animation, even writing and acting in short plays – as you put it, “the medium is secondary to the quest”. Do you come from a creative family yourself? What was your childhood like, and has it shaped or influenced your approach at all?

Oh wow, what was my childhood like. Psychoanalytical right off the bat!

I come from a very loving family. There’s creativity in my family, absolutely, but neither of my folks are artists. My mother does have the most beautiful penmanship in the world, but that’s more to do with Catholic schooling.

My mom’s dad was Czech, and to be more specific, Bohemian. He was an engineer, so the idea of figuring stuff out and thinking visually was always part of our language. But really the most impactful aspect of my childhood was the idea that I was always taken seriously, trusted. Even through a classic 80’s style tumultuous divorce family structure, both my folks always encouraged me with respect. Sometimes I’m asked when I knew I wanted to be an artist. I’ve come to realise just how lucky I am, because I never once didn’t know I wanted to be an artist.

If I could put it in an anecdote, I’d say this: My mom once told me that if I was lucky enough to have a dream, I owed it to the world to follow it. I really don’t know how much better a parent can get than that.

Your work has a strong DIY sensibility – or, as you describe it, ‘well-crafted sloppiness’, born of being self-taught – can you tell us a bit about your journey into ‘stuffmaking’ and how your distinctive style has been shaped or matured over time?

There are a few elements of my practice that definitely feel self-taught: woodworking, photography, writing, live action filmmaking, even editing. But I did go to art school and studied illustration and animation, so there is a basis of strong formal training there. I think what telegraphs the DIY characteristic in my work is actually just the product of impatience. There are so many things to do, to try, to make… I can’t imagine formally training in any one field. I’d rather just make shit. That leads to a lot of failure, and I probably spend more time learning a craft while hacking my way through a process than I would if I just took a damn class. But I’m a pretty self centred and stubborn person. I mean, I’m nice, and I’ll definitely help you move a couch, but I don’t really like researching. I’m more into doing.

As for seeing the world through making, I think I can site four paradigm shifts in my life:

When I was a kid, my grandfather and I would sit as his work bench, take scraps of wood, and make stuff, mainly airplane shapes. That taught me how to see objects for what they could be, not for what they ‘are’.

When I was 10, I started skateboarding. Prior to that, a curb was just a curb. Through skating, that curb transformed into an opportunity for self-expression. That taught me to see the world around me with the same fluidity I had come to know individual objects.

When I was in high school, my art teacher Jack Bledsoe made me complete an arduous self-portrait. It took me forever and I whined about it the whole time. But he stayed on me and pushed me and made me produce. Then when I finally turned it in, he told me it wasn’t finished. He instructed me to rip it up and turn it into a new piece. That taught me that art as investigation is bigger than art as accomplishment.

A few years ago I was making a documentary about Tom Mills, my drawing teacher – and most valued professor – from art school. He told me that one’s art has to speak back to its maker. That taught me that if you know exactly what you’re doing, you aren’t doing it right.

You’ve spoken before about how nothing is sacred in the creative process, and you often seem to approach briefs by reframing or rephrasing them. How much time do you spend planning versus doing, particularly when it comes to commercial projects?

With my art practice, planning and doing are the same thing. I really don’t like to plan, I much prefer the process to inform the product. To the extent that art is a product.

With commercials, it’s a shitload of planning. It has to be. Everybody likes to be surprised, but nobody likes surprises. I have found the way to keep spontaneity alive in the commercial process is through arduous planning. You can buy back the opportunity to be spontaneous, but the currency is preparation. Once you absolutely know you are going to deliver, then you can start fucking shit up, having fun. But you have to earn that at every instance. It isn’t accumulative.

Having said that, there was one Ford spot a few years ago where we dropped a truck on a huge plywood box from 20 feet. Everyone on set was nervous. I remember feeling like, well, of course I don’t know what’s gonna happen here. How could I? Who here has dropped a truck on something before? But all the elements were there. Something cool was bound to happen.

As a collage artist, you’re an avid collector, hoarder of things – be that stacks of paper or a 1970s punch clock – often with no clear purpose. What’s the strangest object (or idea) you’ve collected, that you are waiting for the right opportunity to use in a project?

Back in the mid ’90s, when I first moved to New York, I worked with this tiny Ma & Pa production company called The Farm – it was like production boot camp. We had a short-lived studio space on Bleecker Street, when luxury was overrunning NoHo / Soho, so all these lofts were getting gutted for this weird impending digital / tech boom (even though that vocabulary wasn’t there yet). Nobody really knew what was coming, but the upshot was that there was an incredible surge of analogue apparatus thrust into the free-cycling ecosystem, meaning there was a bunch of cool shit left out on the street. I picked up full beam timber and track lighting and vintage office chairs from dumpsters almost at will. But one time I found this crazy photo-enlarger thing on Bleecker Street. Honestly, I don’t even really know what it was, other than it had a huge hood, all these dials, a focusing lens and these arcane legs. It was the size of a teamster. In my fantasy world, it was jettisoned from Robert Frank’s studio (which was on the same block as our studio), but who knows. Anyway, I hauled the thing up to our space and was CERTAIN it was going to feature in some stop-motion animation or something, become alive in some animated film somehow. But a year later, we couldn’t afford the studio anymore and the thing went back on the street. The same street it came from. The end.

The process behind I’m Usually Pretty Good at Naming Things – a documentary about the 100 collages you created without a specific agenda or pre-ordained meaning, in the hope of communicating with your children – was fascinating. It reminded me of automatic writing, but a collaging version of that, the most literal take on trusting the process. As a creative and artist, what did you learn from that taking that leap of faith?

I think I learned that listening is more impactful messaging. I’m speaking in terms of art practice here, not like at a bar, where I usually just talk too much. Listening as part of the process.

For many years, I think I looked at art as wrapping a physical apparatus around an idea. I’d come up with an idea and then figure out how to give it physical form. There was a lot of discovery in that process, it wasn’t just one-off industrial design with no practical function. But when I shifted my focus from completing ideas to making a body of work in which the creation of a piece is part of a larger search, I had to give up knowing that the individual piece would successfully communicate. I wasn’t building words, I was trying to form a language. So I was bound to get a lot of that structure wrong. That’s why I set out to make a hundred, so I knew there’d be at least four or five good ones in there. I just had no idea when they’d come.

I think what I learned about trusting the process is that you don’t get to pick when you fail, but you also don’t get to pick when you succeed, or even how you succeed. It’s life in the aggregate.

As for the documentary itself, it tells the story in a really energetic and original way, driven by the edit. Tell us a bit about how you approached that aspect?

I actually set out to make an explainer film. I felt like a short piece that was a peek behind the curtain of the process— just the formal paper / wood / glue process- would be a cool addendum to the exhibition of this series. Just a video in the corner near the art. But it didn’t work out like that.

When the camera went was turned on me and I started talking about what’s behind the works, I realized just how much I hadn’t realised yet, at least not in prepared words. I had been living inside my head for so long with this series, when I opened my mouth to explain it, I found that part of its magic was that I couldn’t explain it. And that felt kind of scary, kind of irresponsible. I’m fifty; I’m a “professional creative”; my best friend is an architect. All of these things mean I should be able to masterfully articulate the creative endeavour with German precision and Irish charm. But what I found was that I was searching still, that I was relying on this art to help me form an articulation of something every poem has only hoped to maybe just sit with: love.

What happened was this: I caught myself on film feeling very vulnerable. I didn’t mean to, but once I captured that moment, I had to make the film about that. Ultimately, this film was an accident.

It’s not only the visual collages you create that make the work so impactful – it’s the layering and interplay of sounds as well. Do you work with a favourite sound designer, what does the process look like?

I think sound design starts with my relationship to the making process. Sounds are a constant in my studio. In the morning, I listen to the news for a few hours, and then all afternoon I listen to music. I love music, a lot. I also use a lot of different tools to make stuff, and so the making process hosts a bevy of sounds. So when I look at creating a moment on film, I compress the elements that give that moment meaning: space and time are subject to that compression through the physical (lensing and camera movement) and editorial (how many frames per second I choose to use). How I use sound is similar: it’s an element of the collage.

As for sound designers, I absolutely have a favourite: his name is Owen MacLean. We’ve been working together for almost a decade now. Over the years, I’ve given him a couple hard drives of foley I made, but at this point, I don’t have any ideas where the sounds come from. Honestly, what happens is that I send him a film and then we get on the phone and watch it together and I describe what I’m seeing and pause it a lot and say things like “you know what would go great here is the sound of a clamp head sliding across the metal clamp shaft and then like a Phffttt-whirr-BLONK”. It’s like I’m a very low-budget version of that guy from Police Academy, and somehow Owen has the patience to listen to me.

Your films have covered everything from the function of music to upcycling waste into skateboards and the history of chopsticks – what’s been the most challenging topic to bring to life?

Calmness. I am not a calm person, by nature. My brain moves very fast, and I am by NO MEANS implying that I have some unique capability to think more things that anyone else. I just mean that I am probably undiagnosed ADD, impatient, fearful of death, intrigued by chaos, inspired by order, and dedicated to other opposing forces, like creating art and obtaining money. So finding calmness and learning how to communicate that with meaning and sincerity is an elusive endeavour. I guess that’s what slow-motion is for.

What are you working on at the moment?

Our family spent the fall in Hamburg, Germany, as fellows / artists in residence at The New Institute. It’s a pretty incredible place that hosts academics through fellowships and tries to bring people together to think on ways to make the world a better place. The way they work is that they invite academics to live there, continue their own work, but also participate in programs defined by the Institute. Those programs change each year, but this year one of them is Black Feminism and the Polycrisis chaired up by Minna Salami. When we arrived in the fall, Minna asked us to collaborate with her and the group to create a dynamic short film that explains what the Polycrisis is, and how Black feminism is uniquely suited to address it. So that is what we are doing– making a short (four-minute) film that Minna and her team can use in the world to advance the discussion.

I also completed 24 collages while I was there, in a series of 48, called We’ll Figure It Out When We Get There. Using materials obtained locally, I asked those shapes and images to come together as mini-narratives and abstracts, interpretations of my intellectual and emotional experience at The New Institute.

I’ve also got a few pieces in a collage exhibition in Valladolid, Spain this May and June as part of ‘Las Raras: New Voices in Contemporary Collage”. It’s being curated in part by Maximo Tuja https://maxomatic.net/ who is an incredible artist and even incredible-er steward of current collage. Through his podcast The Weird Show https://theweirdshow.info/, he’s interviewed hundreds of collage artists over the past decade, and greatly contributed to the form.

Other than that, I’m just trying to be a good partner, stay afloat, make art, somehow continue to afford to live in this increasingly alienating financial maelstrom that was once the city I loved, and most importantly – be a dad.

INTERVIEW BY SELENA SCHLEH

INFO:

Mac Premo website

I'm Usually Good At Naming Things

Filmed by Mac Premo & Srdjan Stojiljkovic

Edited by Mac Premo

Sound Design by Owen McLean