Sad Night Dynamite, Vol 11

You’re currently based in Toronto but grew up on the Canadian prairies – tell us a bit more about your upbringing and background. Were you creative as a child?

I grew up in Alberta with parents from rural backgrounds who both went to art school and had worked as painters and graphic artists before having kids. So I got an amazing creative education sitting around the dinner table with them and their friends, but also picked up on a lot of the practical skills that they amassed living on farms and working in trades. I’ve been working with tools, drawing and making little films for as long as I can remember so I always expected I would end up doing something creative.

After studying for a degree in film production, how did you get into the industry?

I went to film school in Vancouver and the classic route after graduating there is to be shuffled into production on made-for-TV movies from LA that come up to shoot cheaply. My specific role was adding digital snow into Hallmark Christmas movies shot at the height of the summer, which paid the rent while I spent evenings and weekends hustling to get my own directing projects off the ground.

Sam Tudor’s Joseph in the Bathroom

References such as Magritte’s painting Not to Be Reproduced in the opening shot of Sam Tudor’s Joseph in the Bathroom video hint at a strong surrealist influence in your work. Is it an aesthetic/style you’ve always been interested in? Where do you find inspiration?

More and more I find the surrealists and their trust in the illogical to be a huge source of inspiration. I am mainly guided by atmosphere and feeling in my work, and have been making an effort to let images and ideas flow through me without judgement or a need for obvious meaning. Sort of imagining myself more as an antenna as opposed to a generator of narrative images. And then working backwards from these sensations to unearth solid concepts. What I find most fascinating with the surrealists is that they understood the images and ideas that emerge from the unconscious can be more emotionally affecting than those which we clearly understand.

Magritte is particularly interesting to me because a lot of his work is not purely abstract, with some sort of grounding in reality. This tension between the real and the imagined can be used to great effect in film, because in the era of photorealistic visual effects, we can create an experience that forces the viewer to accept inversions of logic as real, like in a dream (screwing with physics, time, scale, space, etc).

As far as general inspiration, I spend a lot of time walking around my weird neighbourhood in Toronto, riding public transit and trying to keep my senses open to grab onto strange or interesting things I encounter.

In your Sam Tudor videos, the visuals have been guided very closely by the lyrics (in Joseph…, the lyrics became the script in essence) – is that generally how you approach a music video brief? Or does it depend on the individual artist and track?

It really depends on the project. One of the amazing things about Sam’s writing is its vivid narrative nature and having both grown up in Western Canada, we have a lot of the same reference points, so the stories in his songs manifest really clearly in my head. For me it made sense then to treat his lyrics as a script and then to pile visual elements on top to reflect the emotional undercurrent in the music, where the abstract imagery serves to get to the core of the story’s emotional message.

But there are all kinds of projects where this isn’t the right approach. I think being too literal can actually dilute a good song in the same way a film adaptation fails to capture the imaginative experience of reading a novel. And then there are tracks that don’t tell stories and instead offer more vague sensory experiences, where the visuals need to be an expression of feeling. In either case I think the best music videos find the heart of what the song is communicating and spit it directly onto the screen, hopefully pulling something out of the track that you might not immediately notice in listening to it.

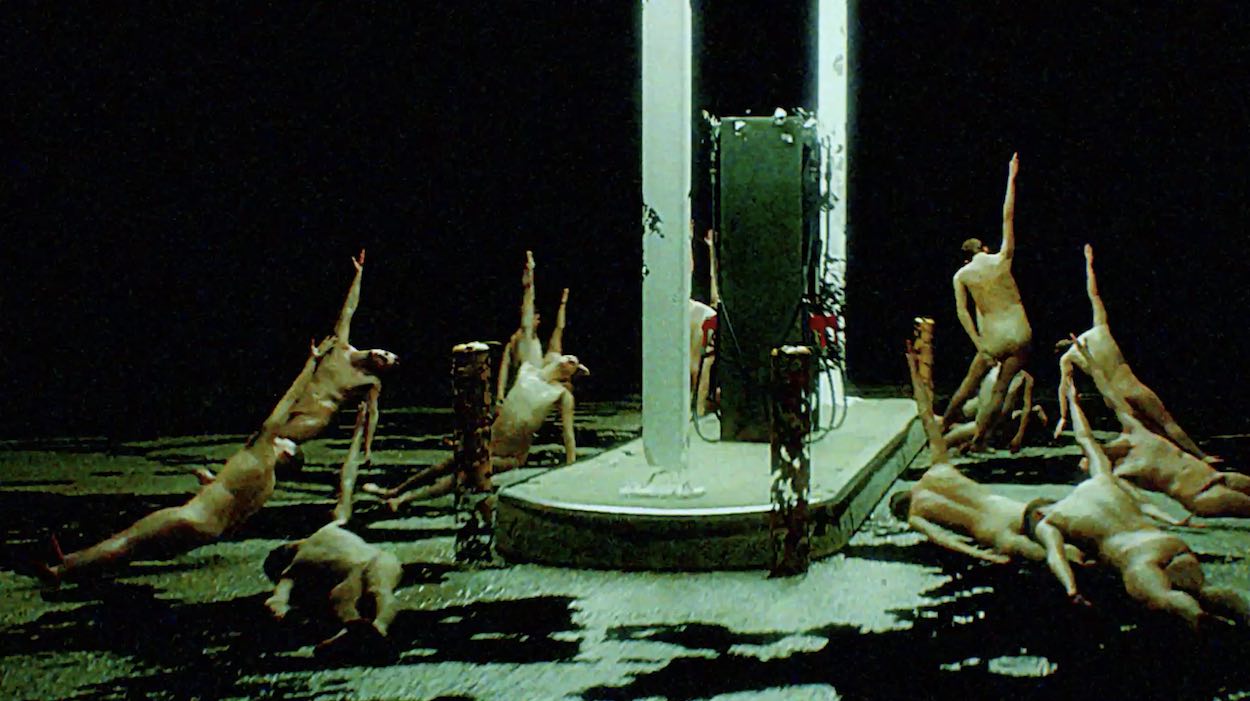

Sad Night Dynamite, Vol 11

You’ve made a name for yourself with cutting-edge VFX techniques – all the more impressive given that you taught yourself. Most recently, you used volumetric capture to great effect in Sad Night Dynamite’s Volume II – what were the biggest challenges in working with this tech, and how did it push your boundaries as a filmmaker? Is there any other tech that you’re keen to explore in future projects?

Getting access to Dimension Studios volcap stage was an incredible opportunity because I am so used to coming up with low-tech VFXs solutions that will work on tiny budgets (lots of fishing wire, etc) while trying to make the images feel seamless and high-end. But what’s really interesting about volumetric capture is that it’s still in its infancy and comes with a host of limitations, and these constraints actually ended up defining the aesthetic approach.

Essentially, volcap involves sticking the performer in a cage rigged up with loads of cameras that capture the action from several angles. And then this data is fed into processing software that spits out an animated 3D model which can be placed in virtual environments or comped into live-action footage. This offers lots of flexibility but the models are fairly low resolution and come with digital artefacts like jagged edges and holes that most filmmakers try to obscure. For me these faults had a really unsettling quality that perfectly lined up with aesthetics of Sad Night Dynamite’s music, so I decided to lean into the fragmented feeling and leave it out to rot on the table.

The other major constraint is that the volcap stage is small and the performers are physically restricted in how much they can move. So all of the dynamic elements of the film, like camera movement or the spatial relationship between actors and set needs to be happening in your head. There is no opportunity to actually “see” the shot outside of your mind’s eye, so this requires a shift in thinking from a traditional live-action approach. You essentially cleave the directing process into two halves: one on the day where you focus on a getting stationary performance, and another in post where you build literally everything else. This takes a lot of the directing work into post-production, where things become painterly and experimental – adding and subtracting elements, messing with timing and angles, etc. This was very challenging but wading through the experimental soup and having the tight level of control was very rewarding creatively.

As far as other technologies to explore in future projects, I think the most interesting thing happening right now in imaging is the rise of machine learning. We are going to see an explosion of completely new images as the scientific research starts moving into software that filmmakers can use without intense programming know-how. So I’ve been keeping my eyes on the research and dreaming up ways to integrate it into films once it is a bit more accessible.

Sad Night Dynamite, Vol 11

In Volume II, which is set in different versions of purgatory, time seems to dissolve. Both time and reality seem to be malleable constructs in your work, what interests you about these themes? Are there any other topics you’re keen to explore in future projects?

I think the modification of time and reality are actually the most fundamental tools in cinema. Film is arguably the most accurate form we have for reflecting and recreating human experiences, but its ability to stretch, compress, delete and repeat time allows us to tap into realities beyond the normal limits of perception. And so there is a whole world of new and powerful experiences that we can find by playing with it, which I find extremely exciting.

On this SND project, the guys were trying to reflect a sense of being stuck in purgatorial looping time, where there would be no distinct beginning or end to the 7 individual films. And conveniently, because they would be presented on social media where moving images loop by default, the platform really lent itself to this concept. All of the pieces function as self-contained units where time and space have no head or tail.

One other theme that has been rattling around in my skull lately is the tension between body and mind. As I get older, I’ve been having visceral flashes of awareness of my fleshy hull, and I’ve been trying to find a way to capture this sensation on screen.

Sad Night Dynamite, Vol 11

Much of your work involves hours spent alone working in your home studio – no budget, no crew – is that something you thrive off? What does the creative and production process typically tend to look like for you?

To be honest it has been a matter of necessity for an early career filmmaker. Any time you get VFX involved in a project, and particularly when you are working with a studio, the costs just skyrocket, and understandably so given the massive amount of work and skill involved. So I tend to take on the post work for practical purposes. I will say however, that being involved from pre to post-production allows me to experiment and discover new ideas along the way as well as shrinking the distance between mind and screen, which is more challenging when you have to translate a set of ideas to someone else. That said, I really welcome the opportunity for some bigger budgets that will allow me to fairly collaborate with other artists who can bring new perspectives to the work.

Now you’ve signed to Blink, what do you have coming up next?

Signing with Blink has burst open the doors to working with artists and labels I admire, and they are just such a nice group of people who are driven to make cool work. I can’t specifically speak about projects on the go, but there are a bunch of music videos we are trying to get off the ground, which will hopefully lead to bringing my sensibilities to commercial work.

Interview by Selena Schleh

@lucashrubizna

@blinkstagrammer

Blink website