Your path into filmmaking is an interesting one: you studied philosophy and worked as a model before doing a Masters’ in illustration at St Martins. Was art and film something you’d always been interested in, and do you come from a creative family?

Yes, it was a little bit of a windy road to where I am now, but you guessed right; my family is extremely creative. Both of my parents are architects – my father still has a practice in London aged 80 and spends his time on holidays painting and drawing. We grew up visiting galleries on weekends, marching around old palazzos on holidays, and always keeping sketch books. My dad taught at the Royal Academy in London for many years and all of our godparents are architects or artists. And just to push it back another generation, my grandmother was an amazing portrait painter and sculptor, and my grandfather was a sculptor who was made to design cars and vehicles during the Second World War.

So when I decided to study philosophy at Cambridge, my dad really encouraged me and told me the creativity would always be there and it was a rare opportunity to develop my mind in an unexpected way… and then I could turn my attention back to art. I had thought I would like to be a painter for most of my teens, but something to do with having a gap year, and this sudden way of making money by modelling, side-tracked me. I grasped for freedom and decided not to go to art school.

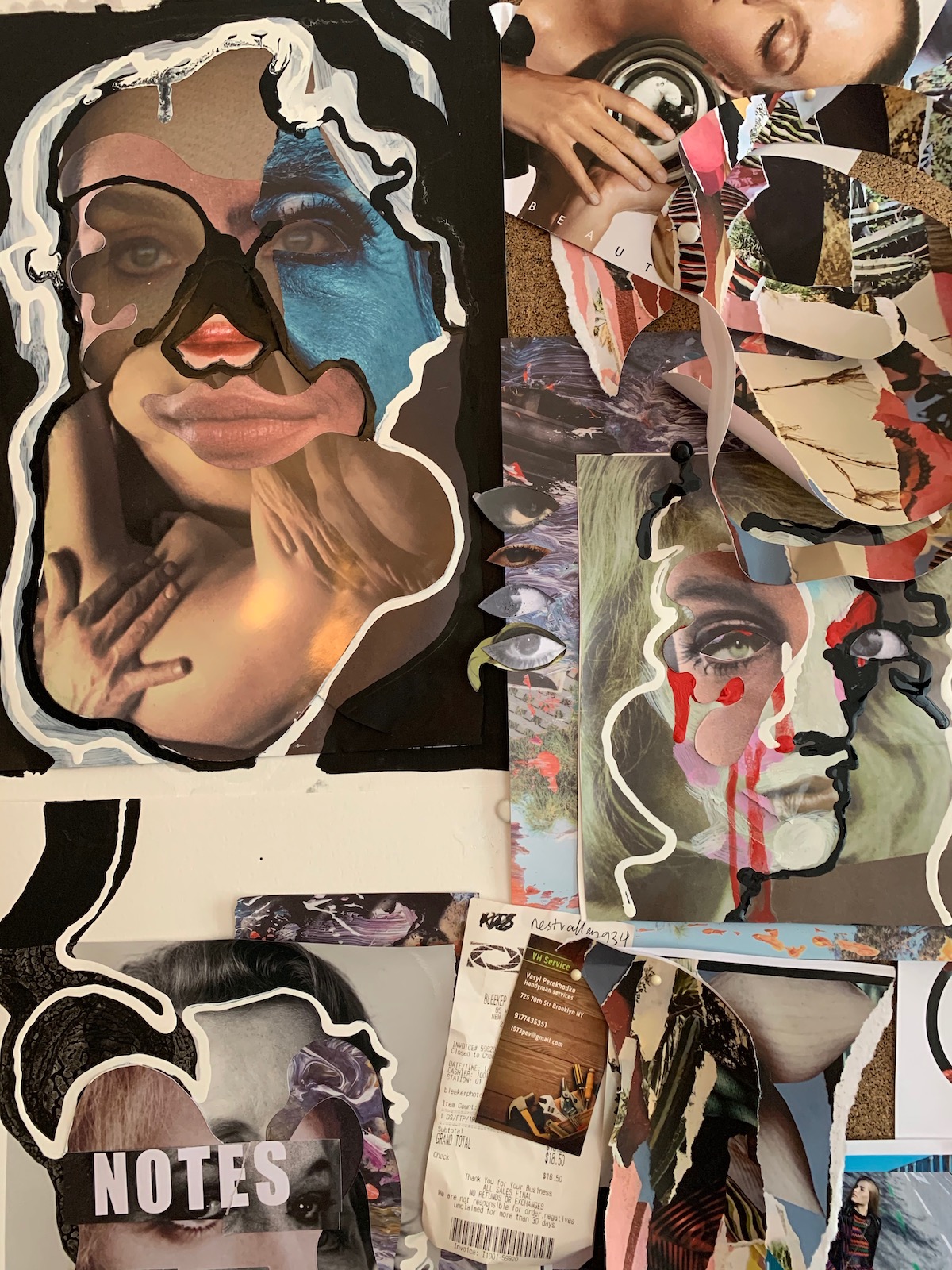

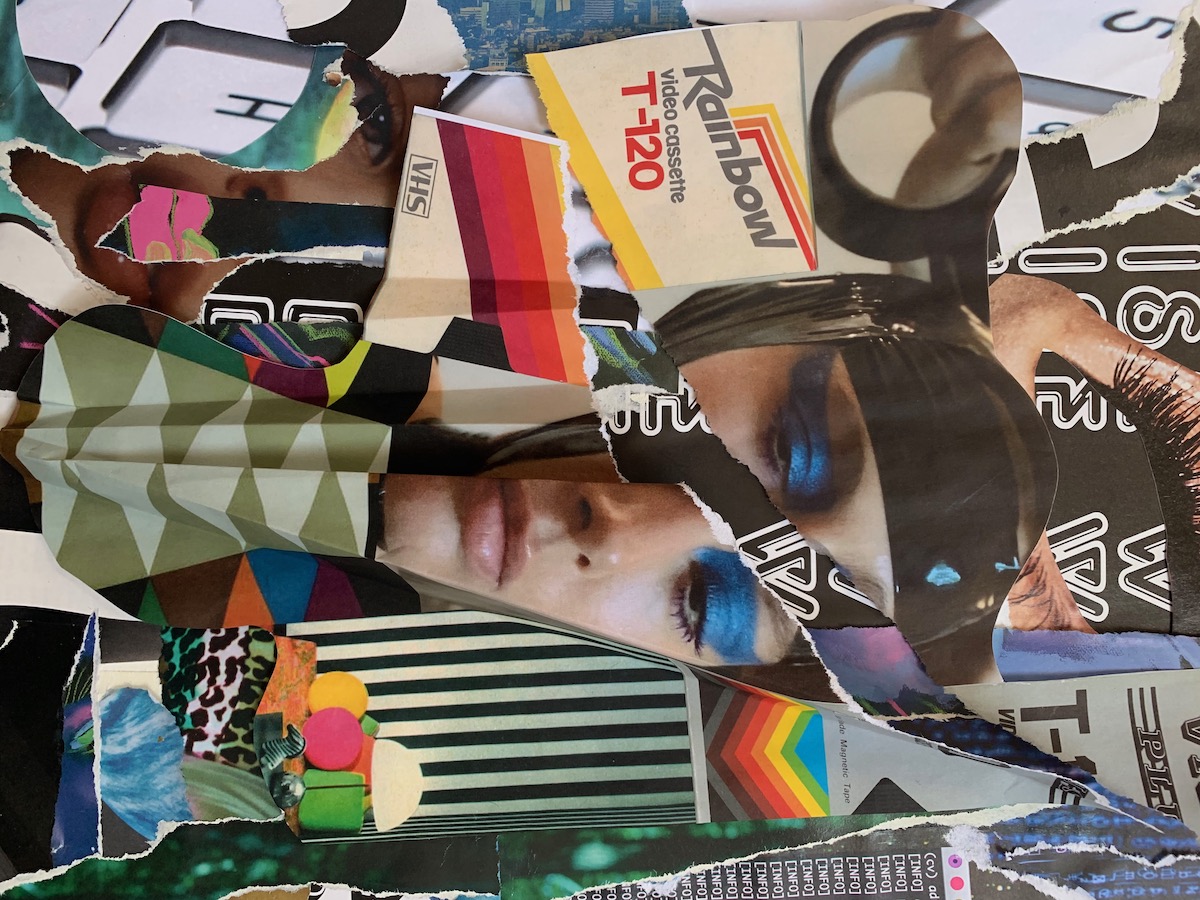

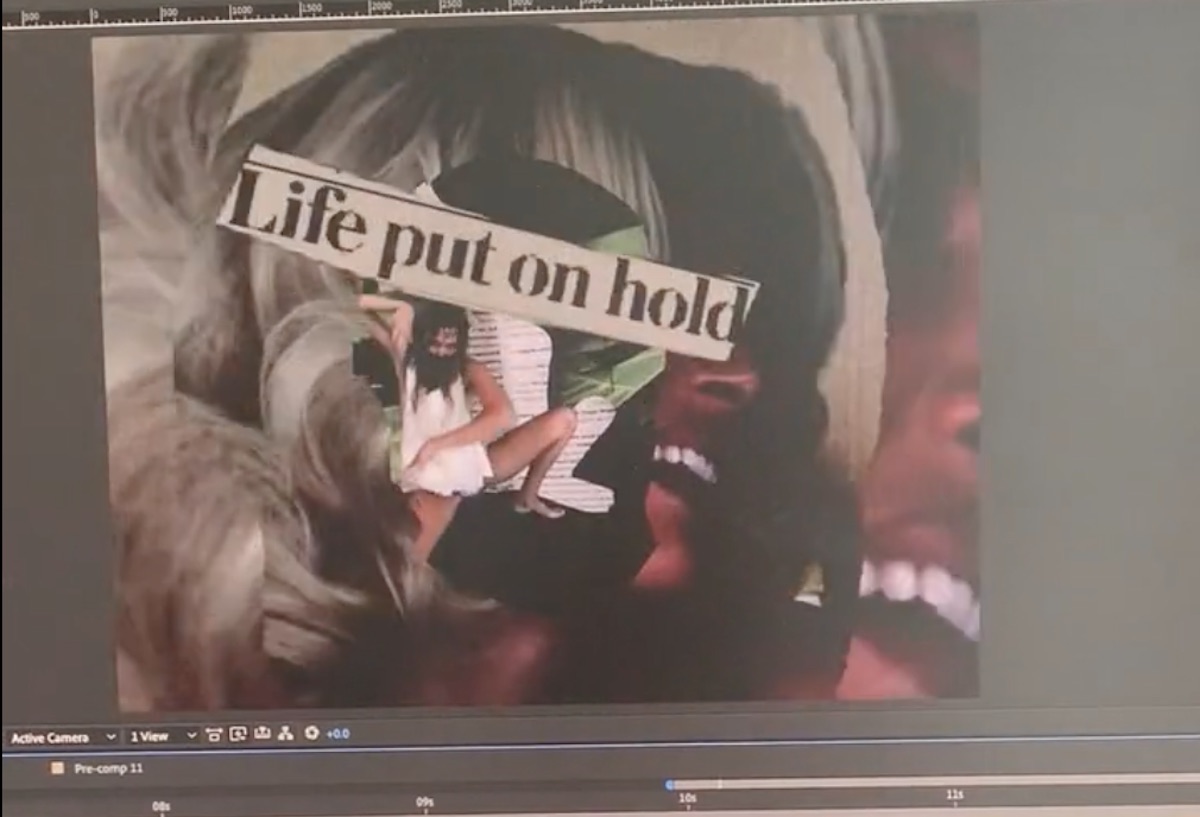

Then, when I started at St Martins for my MA, I panicked. I realized I didn’t want to be an illustrator, in the classical sense, so started to collage and create large scale mixed media works. While I was there, I got into the habit of photographing my pieces as I worked on them, in case I messed one up or just to save some of the pretty half-done moments. By chance, when flicking through my images, I watched the paintings come to life in stop-motion… and had my little eureka moment. I would make moving collaged paintings for my final show. It was a matter of months between then and realizing I could layer my moving artwork with live action of people. Suddenly I was reminded of the Svankmeyer films I would watch as a child, and the stop motion movies I used to make with playdough and my mum’s camcorder. So, weirdly, I was tapping back into something I had loved, then forgotten.

How and when did you first start combining static photomontages with film?

As I said, I only noticed by chance that my collage and paint work was interesting in motion – but of course, getting from there to making films with live footage, and moving animation weaved in at a commercial level are two quite different things. And I have to say I never learnt anything properly- I just figured out the Adobe programs while making experimental films for magazines and very low budget projects. The blessing of no money at the start of your career is often underrated!

But I look back at my lack of knowledge and wince now – I literally did every single frame by hand, which I hoped looked ‘charming’ but often just looked really scrappy. When I first started working on commercial projects with this very unusual approach, and clients would ask for amends, I would just take a deep breath and explain not much was possible to change. We shot the ‘live action’ with thousands of stills at that stage, because I wanted to be able to print each frame and cut into them with my scalpel or paint on top, frame by frame. A film would take months.

In the years that followed, and as my teams got bigger, I started to learn from my professional animators. Now (finally) I would count myself as an animator – and films have to be turned around in weeks, not months. But I think the way I started making films still informs my vision for filmmaking.

Your work has a very distinctive aesthetic that’s been described as ‘modern surrealism’. Where do you draw inspiration from, and do you feel like your style is still evolving?

Always evolving, or it’s over! I am so in love with learning new aspects of my craft and challenging myself. I had been so resistant to learning 3D animation – I always had people who could do it for me. But during lockdown, I thought fuck it, let’s buckle down and face up to a challenge. So I set about doing a 3D project where I had a chance to dive around and learn all about the virtual camera moves.

As someone who also creates the artwork in the films, it was so liberating being able to see how exciting your 2D collage becomes once it is pushed through this type of technology. I really want to go further into this and am plotting some sort of experiential video art show at the moment. That would be a dream to work on: a hugely interactive world of moving art that your audience can walk through and be immersed in.

What’s the starting point for you as a creative? Is your process very structured, or more organic? How much do you sketch and board out in advance?

I would say that it starts off with a wide net, and I just try to open myself up to whatever new or old resources or references are out there. I try not to look at the work of my contemporaries, because the thinking can become quite cyclical and narrow. When life wasn’t locked down, I would try to go to museums, with at least as much time spent in their bookstores. I will take pictures of artists who I haven’t heard of before, and take reference snaps on my phone. This is usually where the overarching idea for a project will come from. Then, back in my studio, I will pad out the idea with extra references (from my colossal, ever-expanding reference library, that only I know my way around).

Once I have, say, 400 images that have the right feeling, I start to build decks and sketch ideas. Explaining things to a client is always a bore, but the process ultimately clarifies the idea to yourself. So I go into it feeling like having a tantrum, and come out feeling confident about the project.

What prompted you to try out narrative filmmaking in Eve Before, and how did you find the experience? Is it something you’d like to do more of?

I would love to move more in that direction. I have been working on my first feature-length script this year, but it is a labour of love and by no means finished. It would be so amazing to see that come to fruition, especially as I so clearly know what every single frame would look like. When I can fully imagine something (in the true sense of picturing it in my mind’s eye) it is a sign that it is going to work well. There are projects where I just can’t see the client’s vision… and we don’t need to discuss those!

Depending on how lockdowns and life go this fall, I might try doing another self-shooting film but make it a fully scripted 10-15 minutes, just to play with the techniques I learnt with my first lockdown film. [It would be] another short narrative film, where I am totally in control, and can be spontaneous in its creation.

Let’s talk about your ‘quarantine chronicle’, It Was Fine. It feels like an interesting comment on lockdown and creativity – some people found quarantine a rare opportunity to be creative and productive away from the shackles of normal life/work commitments (as the voiceover says, “How marvellous to have a little time for self-discovery!”) but for others, being stuck inside, in their own heads, without external stimulation and their usual sources of inspiration, was mentally very tough and potentially creatively paralysing. Your experience of lockdown – three months in a New York apartment – feels like a mix of the two. Can you talk us through the process of making the film, from initial inspiration to editing everything together?

Despite this not being the first time I’d made a film of myself, it was definitely the most ambitious project I have done with no real ‘help’. I had an amazing team doing the costumes, hair and makeup and sound. But every single other aspect I just figured out and filmed in my spare room. Just like you said, this project was a rare opportunity to do a deep dive into lots of creative things I had been wanting to try or to learn.

I have to say I needed to do this project, to feel as hopeful and as in control as I could at the time. Having something to focus and work towards was such a blessing in a time that was otherwise so out of our hands. And I loved the way I worked on it – for instance, I created all the collaged backdrops just with a sense of the aesthetic and themes, before I shot anything. In that way I could be really free and work intuitively as a collage artist, and not being restricted by what I knew I had shot or what I needed.

Then it came to shooting myself in a room alone, just using my Canon 5D against a greenscreen I bought from Amazon. I also had to figure out the lighting, which was kind of empowering knowing you can do stuff by yourself, and all the animation and edit was me, which again was so much more engaging and enjoyable than the commercial process can be. That’s not to say I am perfect in any of these fields (far from it), but it was very cool to realize you have a broad understanding of how to make a film from start to finish by yourself.

In terms of the themes, I wanted to play with the sense of one’s inner world in contrast to the realm of public information, and also one’s public/social media persona in lockdown. I love that there was utter nonsense and insanity at every level, as we dealt with a very physical/scientific reality. And I think more than anything I wanted to create something fun to watch, which was visually a little weird to echo all the layers of craziness we were feeling.

Like a lot of your work, It Was Fine demands repeated viewing – there’s so much going that you notice something new each time. What were your main references, both visually and in terms of voice over?

That is so nice that you watched it more than once! Visually, it was really to bring a lot of my fine art and collage loves into film, which on my mainly commercial schedule isn’t usually possible. I wanted the characters to live in rooms of art that feel like differing levels of mania, and I wanted the camera to never stop, to keep flying from one scene to the next with no edit points, almost like endless scrolling online. The days that roll into days, and then weeks and months, much like when you get to that ‘all caught up’ moment of shame on Instagram.

I hoped that the voiceover would bring lightness to the piece and make it funny at points, because it felt important to have a lightness of touch. I am ever aware of how lucky I am to be healthy, and still working in this grim time. I wanted to create something that wouldn’t be too loaded or heavy, and instead be entertaining, while also strange and thought provoking.

You conceived, shot, edited and produced the film – how long did it take from start to finish, and what were the most challenging aspects of the process?

The most stressful thing were the days leading up to the shoot days – all the ‘what ifs’. Usually I have teams of people to run my obscure or demanding ideas by, who can verify if they are doable or will work in post. and this one was more of a ‘suck it and see’ approach, which had its upsides. Because I wasn’t wasting/spending any money it didn’t matter if some things didn’t work as planned, and then of course lots of things came to me on the day of shooting.

But as soon as I brought on the stylist, hair and makeup artists I suddenly felt like I had people to let down… and that is the real stress for me, making everyone happy with the project. Hence why I am thinking about doing something next that is even more raw, more script-led, and just me working on it. Now I know what I can do by myself, it seems mad to not try to push it further and also make baby steps into a more narrative world.

Click on thumbnail to see work in progress

Are you working on anything else at the moment?

The feature script, many pure art-based stills projects, as well as potentially a new self-filming project. On the commercial side, I have a few new projects coming up in the beauty and fashion area, which always is my comfort zone.

I can’t wait for everything to get back on track with the industry – I miss the frequency of being on set. It is one of my favourite things: the camaraderie and collaboration of all the special minds that make up our teams. Despite having a lot of fun and learning a lot going it alone, you can’t beat the magic of the teams on set.

Interview by Selena Schleh