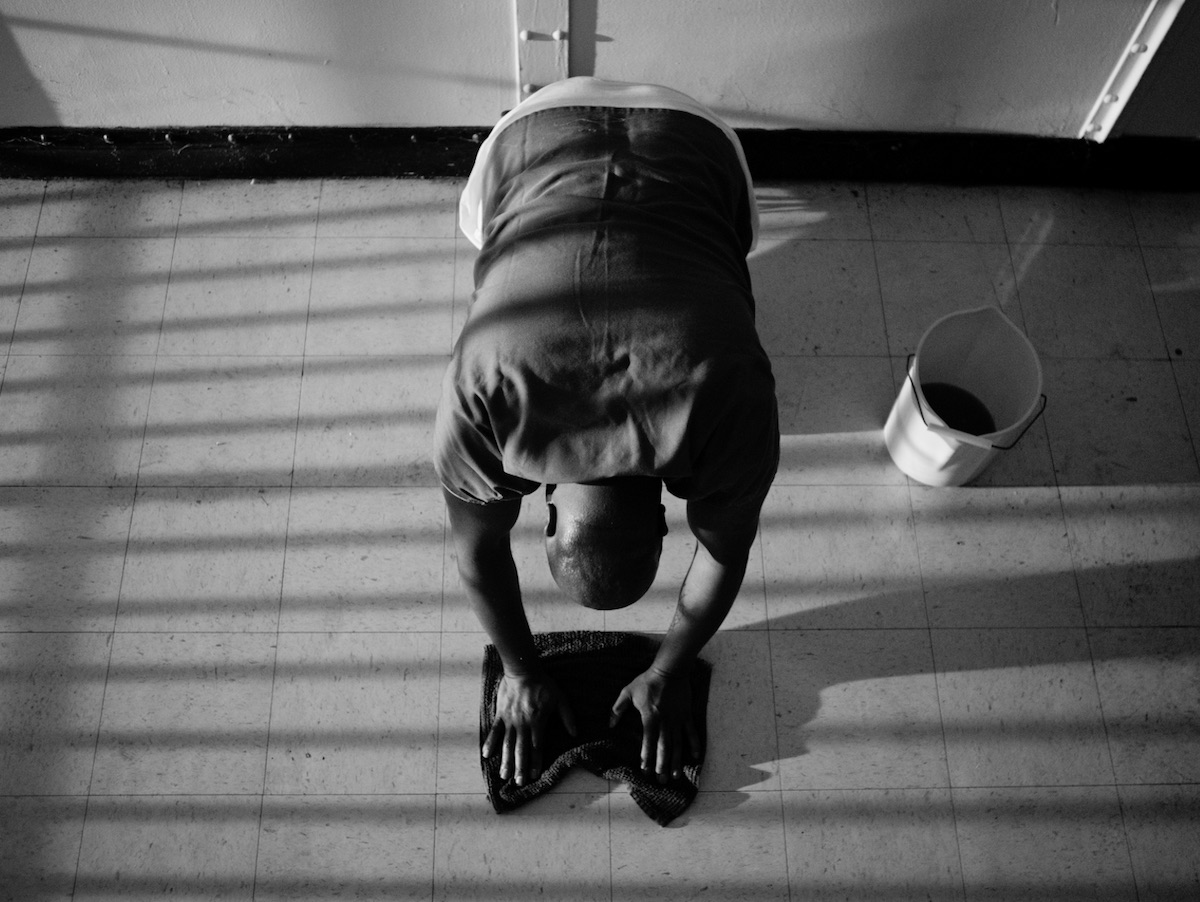

Actor Skeeta Jenkins and Bilal Haider on set

Your personal ideology is a very simple one: “create”. How has that led you into a career in directing?

I think I’ve always had this affinity for filmmaking, because it is that ultimate form of creativity. It’s art, music, performance and writing as one single entity, and many of the filmmakers I worshiped growing up gave me experiences with these combined elements that’ll stay with me for life. I want to give experiences like that back through my work. I think my personal ideology to simply “create” is one I have in order to keep myself hungry, humble, and remind myself why I make what I make. I think without simple words to live by, a lot of artists can lose track of the ground underneath them.

How is your directing aesthetic shaped by your perspectives and lived experience as an American Muslim?

The Prisoner’s Song, and many of the films I want to make going forward, have this common through-line of focusing on individuals impacted by stigma and dehumanization. I think a large part of why that narrative inspires me is from growing up in a post 9-11 America. I was born in ’98, so for most of my life, I grew up watching films and TV, and consuming national media where Muslims were portrayed and spoken about inhumanely, when a lot of the perceptions about people like myself, my family, and fellow Muslim Americans are just not the truth.

I also think that Islam has such a visual intimacy to it, from how we wash ourselves for prayer, to how we pray, and so on, every part of it is beautiful. I think those aspects of my religion have shaped how much I value the look of my films, caring more about performance, shot composition, blocking, and aspect ratio, rather than a grand monologue.

The Prisoner’s Song

The inspiration for The Prisoner’s Song came from a very personal place – you and your crew have friends and family caught up in the prison system. Can you tell us a bit more about the genesis of the idea?

A couple of years before we decided to make The Prisoner’s Song, me and my producer/co-writer James Rozelle would talk on the phone for hours about how ridiculous the circumstances in the United States were for incarcerated Americans. We are the most incarcerated nation on this planet and much of this country’s economic and political structure rely on that, which to me is just saddening.

My co-writer was particularly passionate about the topic just from the number of loved ones that he knows who have been impacted by the broken system. So we’d always wanted to tell a narrative about this topic, but it was not until discovering the Vernon Dalhart track “The Prisoner’s Song”, and learning the history of the song – how Dalhart stole the lyrics from an unknown prisoner – did the idea for the film hit us. The song became such an interesting metaphor for the reality many prisoners here in America must face.

Much of the emotional impact comes from the brilliant performance of Skeeta Jenkins, who plays The Prisoner – he conveys so much through a relatively expressionless, stoic face. How did you approach casting?

For each film I make, I aim for natural and realistic portrayals of everyday people, which is an extremely sensitive and risky thing to attempt. No matter who your audience is, everyone can see bullshit when something does not feel genuine, so a completely natural depiction of real people can only work with actors who understand themselves and their emotions comfortably, and don’t just put on a convincing face to play a character.

Because of this, I had to take a very non-traditional approach to the audition process. Rather than giving the actors sides, it was really more of a one-on-one discussion and dialogue about things like their prior work, what kind of directors they liked to work with, how they feel about the subject material, and so on… However, the last question I asked was a bit more personal, and the ultimate tell, to me, as to whether they would work with the kind of film me and my team were aiming to make. I had asked each actor to go back in their mind to their most painful experience of their life, sit in that experience for as long as they chose to, and then without telling me what that experience was, describe “something” to me. This “something” could have been anything: descriptions of items, feelings, thoughts, whatever…

Skeeta’s response was so emotionally vulnerable and raw, he carried this trust with me to go deep into his emotional space, despite us both being strangers at the time. This film needed that bravery for it to work. I knew immediately that he was going to be the person I had to make this film with – no one else. To this day I feel that meeting Skeeta was this project’s biggest blessing. His performance made this film something special, and I’m not only honoured to now have worked with him, but also call him a friend.

The Prisoner’s Song

Did you always intend to present the narrative as two interwoven days, contrasting between the prisoner’s time incarcerated and as a free man?

So many formerly incarnated Americans feel that their sentence never ends after they leave. That was the biggest aspect we wanted to nail, that the trauma always sticks with you after experiencing something as oppressive as spending years in a locked room. I knew that successfully balancing both timelines and having them compliment each other in terms of the narrative’s progression, was key to telling this specific story.

The film’s monochrome palette, coupled with the minimal dialogue, is almost reminiscent of a silent film – was this a conscious influence?

100%. Because the subject material is so touchy, especially during this very chaotic age of American politics, I wanted to make a film that could speak to anyone’s humanity. Silent films from the early years of cinema have this ability to be so accessible, and I think that’s due to it being the absolute purest form of film. They speak directly to the emotions and senses of the audience in a way which dialogue can potentially muddle. It definitely was something The Prisoner’s Song had to do.

And even more than that, it provided such an exciting challenge for me and my whole team. All the talent involved felt like they had this freedom to express themselves in different, challenging, and creative ways. We all would get together as a team and discuss the central goal of each scene, what we wanted to say with the blocking and visuals, and then just try so many different paths to get there. I don’t think that kind of freedom can be achieved when bound by words on a page.

Bilal directing on set

Having explored the justice system and systemic racism in The Prisoner’s Song, and environmental issues in River City, what topics and themes are close to your heart as a filmmaker?

I think that certain topics, questions, or stories I hear stick with me to a point where I want to create discussion about them through filmmaking. I just ultimately hope, more than anything, I do every topic I cover the due diligence it deserves. The reception of The Prisoner’s Song has been amazing, especially from those who have actually been affected by the prison system. I want to continue that in my career above anything else.

After winning a 1.4 Award, what’s next for you?

I’m still quite surprised by the win all these weeks later, and by the reception this film has received over the past year. To have had a film in company with so many amazing films and filmmakers I respect just makes me feel very blessed, thankful, and inspired to push myself further. I’m currently looking for other filmmakers, representation, and producers to collaborate with on scripts of mine, one of those being a feature length version of The Prisoner’s Song, and am additionally planning to shoot a short this year based on a Mosque burning that happened in Texas recently. Obviously as a Muslim American, this subject is the most personal one I’m attempting to tackle, and it certainly will be my largest project yet.

I feel very privileged to have both the resources at hand and the talented team I work with to make my films. As long as I am creating films that can offer a new perspective and sit with a viewer far after the credits roll, or spark an important thought, that’ll be the most important thing for me. Hopefully more success can follow with that.

Interview by Selena Schleh