Let’s just jump straight in to your short film Why We Wake. It seems to be about the effect of an accumulation of damage incurred over the course of life and the recollection of childhood where we were clean of that experience. At the same time it touches on mental health and feelings of helplessness. What drove you to tell this story or what is it about this aspect of human existence that you wanted to explore?

I love that you brought up childhood and that phrase “accumulation of life.” I tend to form personal vendettas against a subject matter through film – I hate depression. I hate chronic illness. I hate trauma. I hate how they ruin marriages and friendships, and people’s inward being and I’ve watched people I love wilt under this cloak. When I wrote this, I hadn’t made a film yet. I’d walk around on set and listen to people talk about burnout in hushed tones to each other. This film was me fighting back against that stuff. It was a letter to everyone I had met who had experienced any degree of depression. I thought, “If I create one film that helps people feel less lonely, job done, maybe I’ve helped someone.”

I very much wanted to explore the idea of escape. It’s funny you called that out – it’s in most of my work unintentionally. I didn’t go to school until 5th grade and my mom was in the hospital a lot growing up as a result of car accidents and more. I often felt helpless over my environment. I had a ton of time in at home and in waiting rooms daydreaming. My escape was to be the kid who dreams of freedom; the one you kind of find yourself staring at who’s a little weirdly fixated on a corner of the ceiling talking to themselves or laughing at the images in their head. Hence, these flashbacks that serve to remind oneself of that innocent hope when we turn to be adults. We run or hide from our demons. I found myself running away at times from those around me who struggled with depression – this film was my exercise of running towards it instead. Thing is, now people meet me and nine times out of ten they literally say, “Wow, we didn’t expect you to be so nice – and happy!”

I didn’t think I would succeed directing; fame, ego and stuff didn’t really do it for me – I wanted to get inside people who felt lonely. Ultimately I didn’t want to make a film about depression or trauma that gave a solution or a pat on the back to anyone. It was made to be an “I get you.” I once had a young man come up to me and say, “I’ve attempted suicide five times and this is the first film that’s described what I was feeling.” It opened up the conversation with therapists and communities and inside of churches who don’t often know how to label medical burnout or depression and now, in my opinion, the possibility of an invisible disease. It really educated me that we all try to escape when we really should dive in and heal with each other.

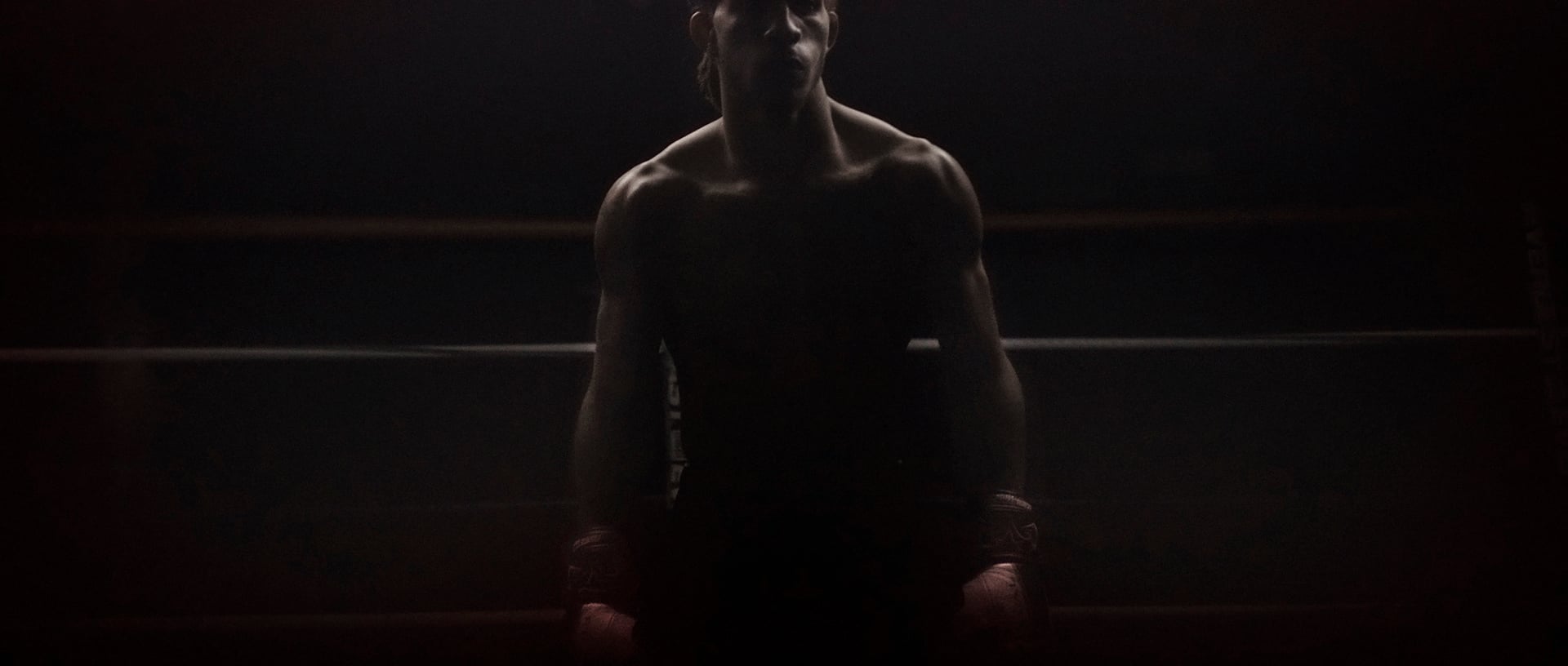

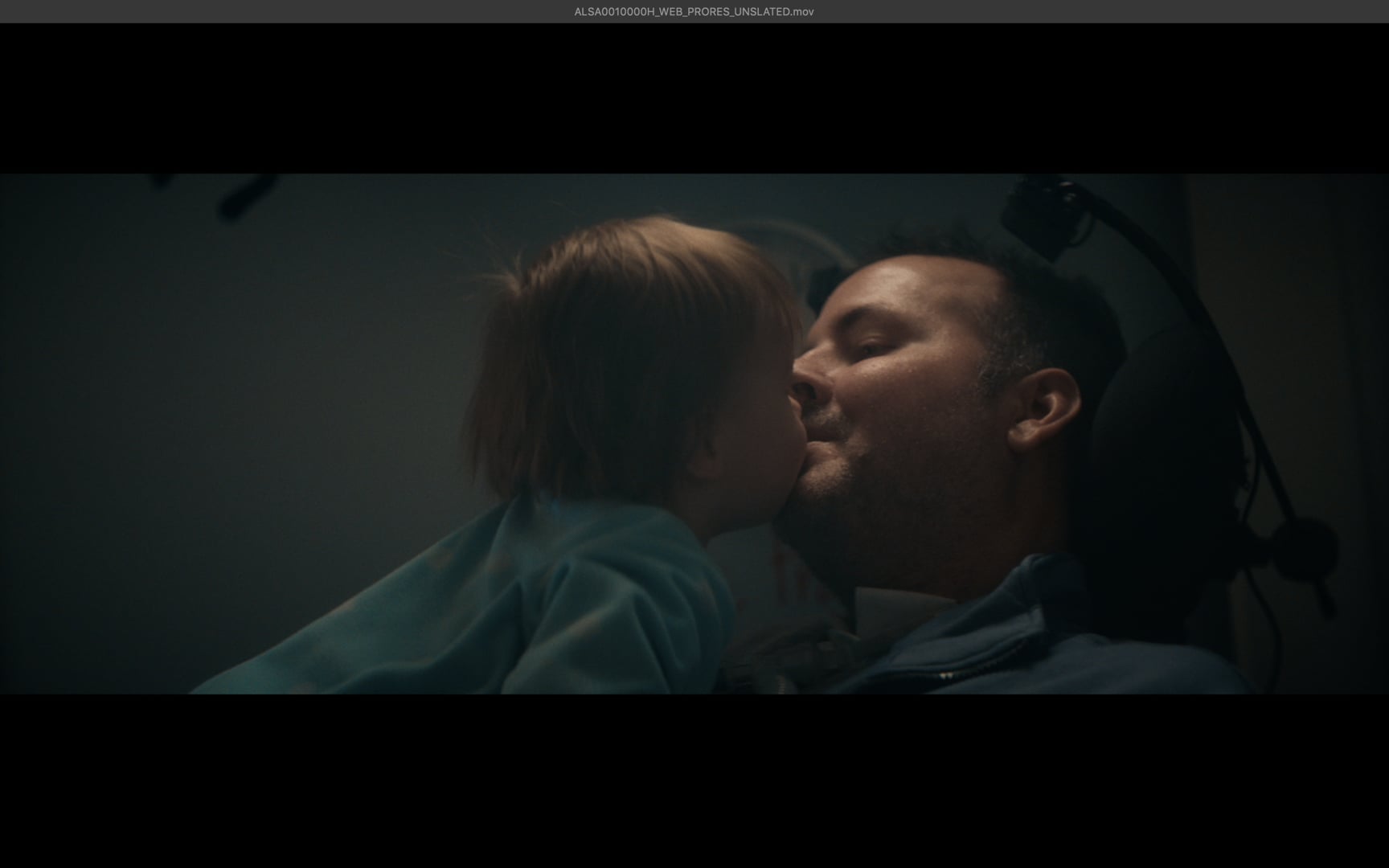

Shooting Why We Wake

In Why We Wake the narrator speaks of an abstract “it” in part of the voiceover, the “it” being a desire not to be alive perhaps? You tie this idea to a struggle against a feeling of lacking freedom that fights against a fear of our ability to take our own lives. How far would you say this construction of a particular mode of the death impulse is one you’ve experienced yourself or is the film more of a thought exercise in trying to understand that way of seeing existence? And why did you decide to explore these ideas through the perspective of a male protagonist?

Well, both. “It” was correctly, death personified to be a character. “It” was anything that seems to take our freedom and joy away. At the time it was a thorough exercise and I had not struggled with depression or thoughts of suicide. I was terrified to release the film actually, because I wanted to ensure the story was true to people who did. That’s why our crew and team wrote it with me who had all experienced depression/burnout/PTSD themselves or in a family member. Those who I knew that had depression which is a very wide term, by the way, used to tell me that the only thing they were scared more of than depression was death.

However, I recently lost someone incredibly close to me and for the first time really thought about the value of my own existence and giving up, as it felt like losing a part of myself. I clung to this film in grief, since I had ended it with a person who chose to push on.

I guess, frankly, I never thought of making the character female. it was simply always a male. Men are stereotypically less likely to sit around and talk about their feelings together, so the internalized nature worked with the VO a bit better. Men also I felt may have benefited from the film more as a tool to share when they didn’t have the words, however females have obviously also written to me about how it struck them which makes me happy the character’s story is genderless even though you see a male onscreen. I generally like to mix up opposing stereotypes in gender and create more reversals on screen – writing characters to be female and casting a male, or allowing my experience as a female to draw out vulnerability within masculinity – or showing a female to be not as emotional as we are often portrayed to be.

With Freddie Stevens, who portrayed this character, we played it as if the camera was his depression, his demon – which is why you often see him shielding himself when faced directly. When the camera is over him, you know in those moments that he’s being controlled, watched. The film changes a bit when you know that and then watch it again. At times, his depression is over him, at times it follows him, at times it’s watching from afar, at times it’s challenging him, at times it’s letting him rest for a split second. He acted more to the camera than to my directing.

In Vive La Victoire you bring attention to Souleymane Guengueng’s fight to bring Hissene Habre to justice. How did you come to hear of this dictator, and how did you go about contacting and building a relationship with Souleymane to tell this story through your short film?

This always makes me laugh to think back to. I had been talking to production companies and many presented strategies to get me into directing was to edit Why We Wake into a :30 pharma thing, or to ‘bring on my all female crew’ to ‘do all the female jobs.’ I was so disheartened. Kathryn Bigelow and Reed Morano were my heroes – they were fitting in what was still then, generally a man’s world. Riding the subway one day I came across a NYT article called, “He Toppled A Dictator. In NY, He’s Just Another Face in the Streets.” it was Souleymane’s story. No one had filmed him yet – this hero who fought for justice for thousands, and a lawyer from Brooklyn (Reed Brody) who was his best friend. The reporter connected me to them and I spent five months learning from them. Their story of friendship and fight for justice is so much wider than I expected (I had only about 1K to get his story made) so the film is a summary that honors Souleymane and Reed for getting a dictator jailed; this is the kind of thing I’d make into a feature one day. Souleymane pretty much schooled me. He kept saying, “I don’t like weak people. I don’t like people who give up.” That project is probably why I kept directing.

Not to Be a Lady – can you tell us a little about how this project came about? How far would you say your own experience as a female director has been impacted by assumptions about gender?

It came about at a bar when a bunch of girl friends and I were talking about how we always felt a bit crazy or had been called the word crazy in the past for the most random of reasons. We were trying to figure out why, and in the midst I wrote a VO about feeling crazy. I decided to film athletes because all over the place, female athletes were breaking stereotypes and as an athlete myself, that resonated with me. I ditched the VO once I interviewed athletes because their statements on gender were so powerful. I don’t feel I experienced any gender bias until directing actually – and it was surprising. It took a year of directing at a signed company before I was thought of to direct a male-centered concept.

However that year is really special to me because I was privileged to be thought of for stories with powerful female Olympians, athletes and more; we need to see more of those stories on screen. Overall however, I’ve felt very respected. I think there are a lot of people out there who are ready and excited to empower a more diverse crowd of directors, and I’ve made diversity, not just gender, to be my goal in hiring on every job. So I guess you could say that I’ve become more aware of the need for diversity than ever before, and also more passionate about championing it.

There’s a specificity to the way you use lighting and color in your films as a way of evoking the tonality of abstract thoughts and memories, almost like a device to dislocate the viewer from reality. How have you gone about developing that style?

I didn’t go to film school or anything, so I wasn’t versed in what made a perfect frame or visual. There was always something really attractive about imperfection in frames that allows viewers to fill in the gaps with their own imaginations. I don’t make films to push ideas on people, so using the tonality of abstract memories and thoughts is in itself the release of the present I think. I’ve developed that style over time by become more grounded in my boards, performance and framework for the story I think, but the visuals are generally in the vein of experimentation meets foundational shots.

I love close-ups. I’ve been trying to go back to my roots actually and allow myself to try out different looks that are risky to explore new emotions and learn as a director what works and what doesn’t. My favorite film is Spike Jonze’s Her and how they shot those flashbacks are so integral to the character’s headspace, story and way of relating to humanity. It’s genius how they used broken lenses and texture to create that – and I think that style will stick with me for my career. I work with a DP as early as possible in the game and write shots in that they think of – I’ll never dictate a shot unless I’m very passionate about it. Once we get a groundwork down, the DP sees things I don’t and that’s how it should be. They should move the camera and light with emotion.

Elle Ginter is represented by Sanctuary

Support services for mental health issues please visit NHS online in the UK and for the States: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/index.shtml