You’ve delved into the psyche of the female character in such a compelling and original way that we empathise, even really like her. Please tell us how you gave shape to this character, did you always have a clear image of her?

What initially attracted me to the poem (written by Olivia Gatwood) was its literary interrogation of the female psyche and the powerful mediation found within it. Olivia is American and wrote Backpedal about her teen years – a personal, post-coming-of-age story that unfolded in New Mexico. I reached out to her when I first heard the poem, asking if she’d be interested in making a film. We ended up talking about how many ‘Australianisms’ can be felt in the story too – and how in fact, it does speak more to a universal experience of womanhood. Macro out of the micro – that kinda thing. And so, our lead was always going to be pivotal.

I hold strong perspectives on the ways that I want women presented in film texts and in many ways, this character was an extension of that. There was a huge risk that these characters could fall into rigid, two-dimensional archetypes, so I was always extremely conscious that our female lead needed to tonally carry the gauntlet. I had a clear idea who she was psychologically, but not physically. That part of the casting brief was very open. I was looking for a sharpness, a sense of autonomy, strength and wit. Her psychology was always going to be unique, and I didn’t want to try and push that into someone’s brain – it needed to already be in there. Brenna Harding is all of that and more. She is an impressive critical thinker with such depth – somehow both delicate and intense. Meeting with her initially, it was clear she understood what I was trying to do with the piece and felt comfortable with the level of abstraction. I knew that Brenna would naturally unfurl in each scene and her intuition would be guiding for the audience. Working with Brenna was one of the most personally rewarding parts of the process actually. She is a dream.

What was your criteria in thecasting process and how did you find the actors?

Both conventional and abstract. Conventional in that we worked with the incredible casting director Danny Long to source our ensemble, but what we did in the room was definitely left of centre. Danny is always open to discussing different ways of accessing performance and she was eager to explore with me. She brought a huge variety of people into the room. We had 5 scenes/actions that we wanted to run but if something more interesting arose as a result – we followed that impulse with each actor.

For example, I wanted the boys to take on a pack like unity and explore some animalistic expression; so I asked them to literally bark like a dog and take it as far as they felt comfortable. It was one of the most revealing exercises I have ever undertaken and it resulted differently for every actor. It immediately gave me an insight into how each actor worked and what they were going to bring to the set. Tom Wilson (who ended up doing the barking in the film) was remarkable. He transformed, and the whole casting room was quieted – it was a real moment.

Otherwise, we mainly focused on shape, movement and group dynamics. Only two scenes out of the five that we workshopped were in the script – all the others, I wrote specifically for the casting, just to see people ‘be’ more than anything else. Our male lead, Michael Sheasby’s first audition was in a group of three and I actually couldn’t ever recall who he auditioned with. He was such an immense force – so striking. If I was transfixed, I knew the audience would be too. It’s that kind of detail more than anything else that I rely on. My memory and instinct always guide me.

I also shoot 35mm portraits (that I print) in all my sessions so that I have a tactile object to remind me of each person’s casting – that is usually how I review and compare. I love putting a camera between myself and an actor early on and just seeing what happens. It can be so surprising. As well as this, my close collaborator and cinematographer Christopher Miles came to our recalls and shot images of each person in character. Because of the intently visual nature of Backpedal’s narrative devices, I needed people to be able to elicit a tone, emotion or story beat in a still frame, so I decided that this process was integral to the film. Chris has an unmatched eye – so having him see everyone’s faces prior to shooting was so valuable. He immediately had so many amazing thoughts about the way light and colour would work with each actor and it made our natural short hand even shorter.

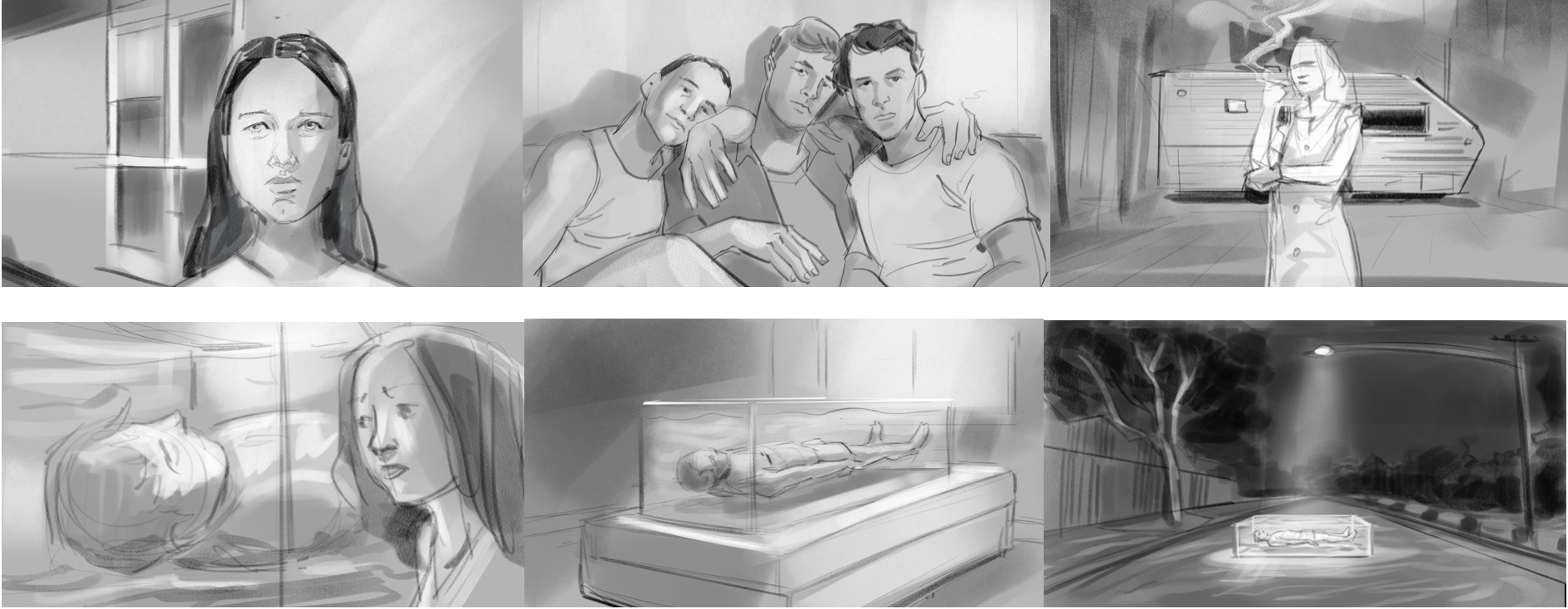

Recall shots taken by cinematographer Christopher Miles

Recall shots taken by cinematographer Christopher Miles

You seem to know these characters so well, what was your directing process – did you workshop extensively?

I love these characters. I know them well, and still think about them sometimes. That affection for characters usually makes me fastidious and detail oriented. I like them to be correctly represented and I’m not ever particularly interested in leaving much of that to chance. I did a lot of research, reading and writing to create “character bibles” for each actor. I believe religiously in the power of pre-production documents and making those is actually how I spend most of my time in the lead up to any shoot. They help me clarify and think further.

The “character bibles” for Backpedal included outlines of who these people were, what I had imagined their worlds to look like, a few key words and a whole bunch of tone reference/imagery. I sent these bibles to the actors and after digesting them, we got into a room and talked about any feedback that they may have had. For some actors there was a couple of notes, for others – hours of conversation. These conversations give me a huge insight into the best ways to work with people and make sure that I am accommodating their needs as well as my own. Getting to know actors as whole humans means you don’t just understand your character, but you also understand your people – and you can find those beautiful places wherein those two things are the same or different. All of this said, with Backpedal I had the privilege of working with some of Australia’s best talent; powerful and intuitive performers with or without my intervention. That always makes the work easier.

As brutal as the story is there is nothing repellently violent. Please tell us about writing the visual narrative – and how some of the scenes came about, for instance what was behind your decision to place the body in the “coffin” on the road.

The opportunities found in a visual narrative of this type were kind of endless – especially when working without dialogue. I wanted to build the world out to be so much bigger than our six minute film could contain and I knew the only way to do that through suggestion and measured ambiguity. The main storytelling device was always going to be the poem, so it was mainly a task of figuring out how I wanted the story imparted to the audience – visually and sonically.

I decided that I would conceive hypothetical scenes from Olivia’s poem world – and then for the film, only shoot a couple of key shots (in most cases only one or two) from that scene. Kind of like baking a cake, and then only giving someone a slice. Someone will assume the shape and flavour of an entire cake based on a slice, right? The film infers most of the narrative and allows the full-blown intensity of our story to exist completely – but just off screen. I also storyboarded extensively with the amazing Maria Pena to ensure this approach would work.

The “coffin” was everything! I am still in awe of our production designer, Simon Morgan, who made that possible. We did all of that practically and it weighed over 2 tonnes by the time it was full of water. The coffin was the first vision that I had for the film – everything was built out around that. Placing the water coffin on the road was very much about a sense of shared loss – the ways in which a community grieve collectively. The idea that this coffin will alwaysbe on that road, because the community will alwaysbare this grief – public and exposed. It was always meant to act as metaphor for the fragility of life and further the stifling, subterranean nature of grief.

Recce shots by Christopher Miles

Recce shots by Christopher Miles

We read you’re working on a feature film – could Backpedal be the basis?

Funny you say. My producer, Sarah Nichols, just asked me whether we should look into Backpedal’s expansion. So maybe! That could be epic. A mini series extrapolation of Backpedal would also be radical too. 6 x 20 minute episodes! It really does have so much fruit to bare in a longer form narrative. Self-indulgently, I also love the idea of adapting a poem to long form and all the challenges that come with that. I’d be so down.

At the moment though, I have two feature ideas in development. The first is based on an individual that I know. It’s deeply felt, personal material. The second is centred upon an unlikely friendship. I won’t say much more than that! While superstitious about nothing else, I am strangely so about the early stages of writing. I like to work in solitude and keep things in a vacuum at the beginning.

Backpedal was completely different from your earlier film Nursed Back, a choreographed film about grief, which we also highly rated. Any more short films in your portfolio?

Nursed Back and Backpedal are my only two directing works thus far. But I’m confident that there will always be a diversity of bold styles and approaches found in my work. Message over medium, always. Whatever feels like the most intuitive, powerful way to express an idea is always going to be what I’m into. All of my favourite directors, photographers and artists are those who are able to traverse genre effortlessly while still maintaining a clear sense of their identity – that’s what I’m interested in. I try to trust myself implicitly and tend to believe that if my gut says it’s going to work – then it probably will. I recently had my first exhibition of photographic works (in partnership with Rob Farley.) We just opened our exhibition here in Sydney and as I do with my films, I feel myself clearly in the work.

Do your stills work and film influence each other or do you have a different mindset for each medium?

I tend to maintain a similar mindset whatever medium I’m working in. I just want to make thought-provoking, meaningful works that are unique to my voice and my perspectives – whether that’s film, photo, installation or beyond. Although a filmmaker first, I am always frothing to experiment and pivot into the unknown.

Please tell us about your latest photography project.

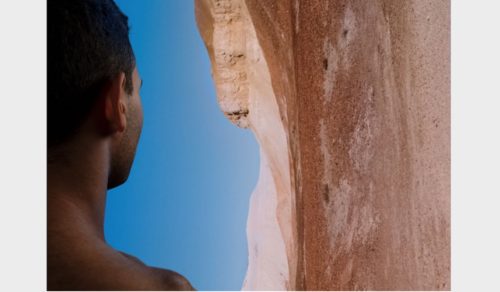

The photo series I just finished with my close friend and on-going collaborator, Rob Farley is titled All Our Strains. We were the recipients of a local grant, The POOL Grant, which is an incredible program that awards one project $10,000 to complete a photographic work. Our project, All Our Strains, is a sanguine deconstruction of the Australian national anthem – we created 54 images that each represent a word that has been reimagined pictorially with the aim to imbue an outdated colonial touchstone with new meaning.

Rob and I went on a ten day road trip from Melbourne to Alice Springs (we drove about 4500km) shooting medium format landscapes/colour scapes along the way. We returned to Sydney, shot a portrait series in a studio and collaged the two components to create our alternative horizons and cultural mirages. Making this project has pushed me not just to think critically, about the hyper-latent ways in which colonialism is manifest in modern Australia but to also figure out – as a privileged, cisgendered, white woman – what actually are the constructive ways to contribute to this dialogue. It’s been a huge, reflective exercise (and will be an ongoing one too.)

Please give us the elevator version of your background to directing. Did you go to film school or learn on the job? And what have you learnt thus far?

I studied Film Theory at university, and actually always thought I was going to be an Academic. That was my plan – I love understanding the world critically and knew that was a valid passion with longevity for me. I was absolutely obsessed by two classes at university – Mass Media, run by Dr. Marcus Breen and Style & Genre, run by Dr. Scott Knight. These two men completely shaped by formative years and encouraged me to look beyond academia. They both told me to write/direct. It’s only now that I realise how pivotal they both were to all of this. (Teachers are saints.)

Having been a Creative Assistant for a long while and learning mainly through symbiosis, I have gone about directing in a pretty traditional way. I started right at the bottom, and worked my way up. I’m extremely lucky to say that in that process, I’ve worked with some of the worlds most lauded directors both locally and internationally – writing, researching and designing treatments. As a Creative Assistant, you are being employed to watch, read, think and refine your taste. If you’re switched on, you’re getting an unparalleled on-going education in film, art and photography. It’s the ultimate. Closely watching established producers and director’s work also gives you a sharp insight into the world of being a working director; how choices and strategy actually play into shaping a career with substance and longevity.

I don’t think that there really is any “right” way to learn how to direct. But, I will say that learning in the way that I have means that I’ve had some key guidance from shrewd advisors who will continue to shape my path. It’s really important to have people around you who see you through the same lens that you see yourself. The Australian film industry (especially FINCH, my Australian rep) is a small, generous, family-like institution and they have watched me grow from a green, 20-year-old into a more defined, 27-year-old filmmaker and artist. These people are like my second set of parents and they’ve been my biggest cheerleaders. That includes Sarah Nichols – my producer and powerhouse intellect – who has tirelessly championed my voice for years now.

Were you brought up in a particularly creative environment – please describe your childhood and where it was?

My childhood was pretty unique. For my first six years, I grew up in a pretty standard, lower-middle class suburb in outer Sydney. Everything was pretty great and normal until, upon a seemingly spontaneous whim my parents decided to take a job in Taiwan. They had never lived overseas before and we agreed as a family – love it or hate it – to live there for a year. Alas, we all fell in love with the country and ended up staying for four years. We also developed a love for our uprooted life together. And so, we ended up moving to a new country every 2-3 years until I was 19. After Taipei, we lived in The Philippines, Thailand, Bulgaria and London (I did my A-levels at boarding school in the UK) — and travelled constantly during our different stints, covering off most of the globe. There is something curious about a childhood saturated with stimuli.

Neither of my parents work in remotely creative fields, but they have this insatiable spirit of inquiry that has defined everything for me. They are inadvertent feminists who didn’t believe in limiting my perspective; challenging me to work extremely hard and to feel self-aware of my privilege. They are hilarious, moral, open-minded people who gave me a perspective on the world that is vastly individual and very much my own. My parents have a curiosity and confidence that resulted in a global adventure spanning almost 14 years – and so, I guess that might be the most bold, creative choice of all?

What’s the next project?

A dramatic short.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

Yes! My current dream. Direct a music video for Stormzy. Ha.