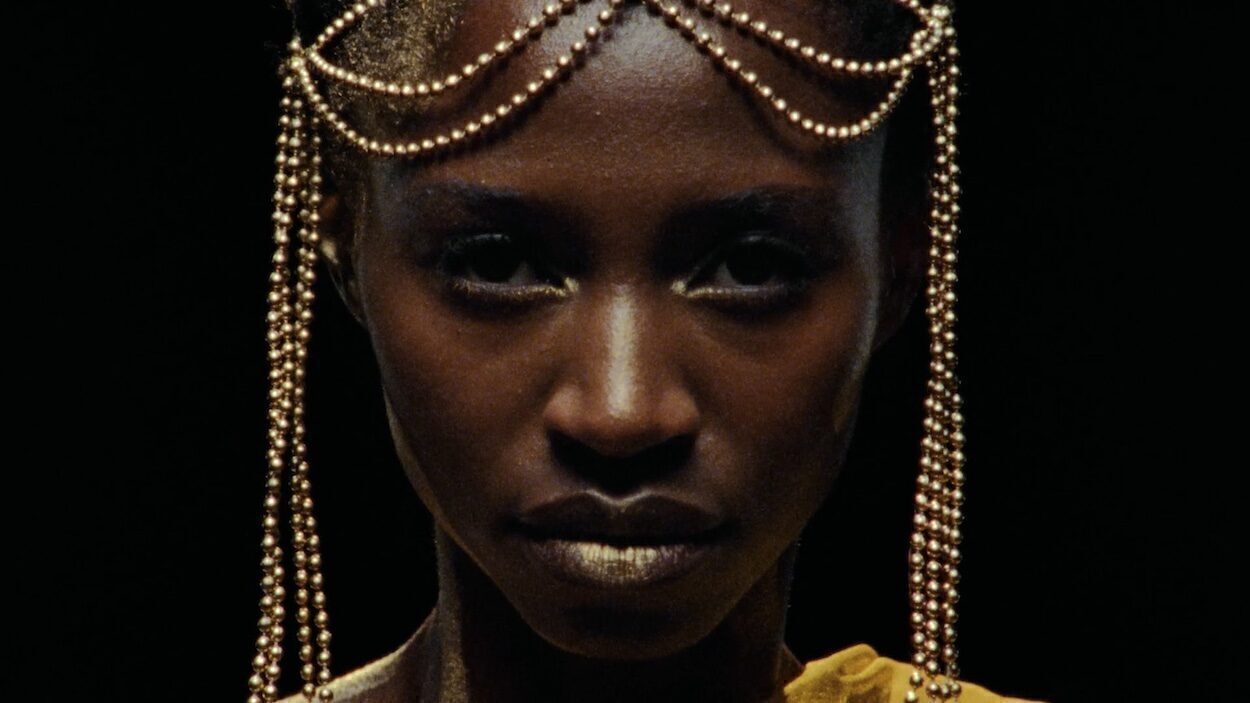

What was your creative process for your visual interpretation of Peter Laberge’s poem? Did you liaise with the poet or was it entirely your vision?

What I love about Peter’s poem is that he combines striking imagery and only fragments of a story to evoke in you a feeling about a significant event, rather than recounting anything directly. This is obviously really useful if you’re trying to find ways of reinterpreting a piece of text as a film. After a few weeks of reading the poem, specific ideas for scenes kept returning to me. The more persistent ones hung around and a simple story emerged.

Both the poem and the film are about a love in the face of danger which is tragically cut short before it ever has a chance to flourish – ‘shot in flight’. This broad story arc is shared between the poem and the film, but the specific events behind Peter’s writing and the scenes contained in the film are very different. Finding where they intersect is what made the whole process so fun.

I didn’t contact Peter until after I’d finished writing the film simply because I knew anything I proposed might feel quite unfamiliar to him at first. As the poet he has his own particular and intimate relationship with the work that no amount of analysis can get close to, he wrote it after all, so I suppose I was worried that my ideas might lose traction if I asked him too many questions early on. Once I pitched it to him in the form of a detailed treatment, he was, to my relief, very supportive and excited to see it.

How did you go about finding the characters and what was your criteria for casting? How did you develop the scenes with the cast – did you workshop / rehearse with them? In fact did you evolve the script with them?

Being a teenage boy in a pack of lads has a relentless intensity to it because it’s so competitive and unpredictable. To try to recreate this I held the castings in groups, observing how the boys played off each other; who’s the alpha, who’s an alpha-worshipper, and who’s just trying to keep out of the line of fire. I gave them some improv scenarios that invariably led to them teasing one another. This helped me find the right power dynamic and revealed those slightly wild personality types who might be willing to push the boundaries.

I also cast three boys who already knew each other from home. This established a ready-made clique, causing everyone else to feel a little on the outside. More importantly though, it placed a high value on aggression as a defining characteristic of the group because these three boys were trained boxers in real life and so naturally exuded the ultra-masculine, potentially violent energy required to make the secret relationship feel unacceptable and risky.

With the two lead roles I was looking for subtlety. I had them tell lies and then encouraged the other lads to interrogate them. The scenario that seemed to resonate most was when I asked them to describe a fictional girl they had hooked up with ‘on holiday’ – a classic made-up story I remember from my teen years. In this case it was acting as a cover story for a deeper secret.

I knew that the two characters from this story would never dare show affection to one another directly, but I still needed to capture the unspoken intensity they both feel. To do this I wrote scenes that are intimate by nature but which are also entirely plausible, meaning they could happen in plain sight without arousing any suspicion. Things like undressing together for a swim, getting grit out of your friend’s eye, or getting inside a big sweater for a laugh. These moments would usually mean nothing, but if you’re harbouring feelings for that person they suddenly become very intense.

One thing which contributed to the heightened atmosphere on set was that only the two lead boys knew what the film was actually about, a secret they decided to keep to themselves. It created an intense real-life duplicity which is mirrored by the story in the film. Also, because I was always throwing in unexpected bits of direction, I think the two of them had a very real fear that I would suddenly ask them to do something they weren’t comfortable with. You can feel that fear in the sweater scene.

The framing, lighting and cinematography bring another poetic layer to the film. To what extent did you map out the storyline before the shoot – it feels very spontaneous. Did you simply have a shots list or was everything buttoned down in a storyboard?

The almost holy quality of Terence Malik’s ‘Tree of Life’ was the primary reference I kept returning to. Also the frantic, reactive camerawork in Andrea Arnold’s ‘American Honey’ was another inspiration. Kevin Treacy, the cinematographer, is a good friend of mine so we were able to spend a good bit of time together discussing how to get the look we were after.

I wanted all the scenes in which the two boys are alone to feel peaceful, serene and most importantly, safe. So these scenes, e.g. the house, barber shop, or roof-top, are always static and composed. To contrast this, everything from the group scenes was supposed to feel chaotic and overwhelming. When all the boys are involved, the camera is constantly moving, trying to keep up like one of the lads.

I mapped out a shot list based on the scenes I’d written, some of which are anchored by particular lines in the poem. Because I’d cast a lot of the lads to essentially play themselves, it was often just a case of gently encouraging them to do things I knew they were naturally inclined to do. I only laboured over multiple re- takes when it came to the lead characters’ performances. Then there were a couple of scenes that were just totally loose, like the swimming, where we just got stuck in and hoped for the best!

Where was the location – was it already a familiar place for you?

Yes it was all shot in Dublin where I’m from. For any Dubs interested, it was the sand dunes and sea at Dollymount, a house behind the graveyard in Kimmage, the old John Player cigarette factory in Dublin 8, and a barber’s in Crumlin.

What was the process of editing the film yourself like? Did the story take on a different shape to what you intended? Any painful moments of having to lose footage that you loved but that didn’t fit?

At one point I was really cursing myself for taking on the edit. But with no money left in the budget I couldn’t expect a good editor to spend the amount of time on it that I knew it needed. I was glad I did it in the end because if I’d made that number of revisions with an editor on hand I think they would have murdered me.

There was one lovely scene of Finn (the main character) exploring the abandoned building which didn’t make the cut. It really was some of the most beautiful footage of the entire shoot and I kept it in the edit for a while. Ultimately though I had to accept that it wasn’t adding much from a story perspective and was changing the pace too much, so had to let it go.

What was the most challenging aspect of the production?

The swimming scene is something I can laugh about now but it was very stressful at the time. It’s hard to describe how cold it was that day. I was standing there, literally wearing three coats, trying to keep a straight face while telling these lads they needed to get in the sea. The light was so perfect and we could see dark clouds coming in so it needed to happen right there and then. While we rushed to prep the camera, the boys were keeping warm on the bus, at which point they secretly conspired to revolt, boycotting the scene by refusing to swim. It was very funny looking back on it. We had to get their Mothers to ‘have words’, as we say. Then out of nowhere my Dad, a hero among us, rose to the occasion and jumped in the water to prove it wouldn’t kill them. He was clever enough to shrug it off like it was no big deal and so the competitive streak in the boys kicked in. I think the threat of being shown up by an old guy did the trick.

What was behind your decision to use the Tallis Scholars as a soundtrack with the poem’s voiceover? (The juxtaposition of the sound with the punchiness of the visuals is inspired).

The poem has strong religious themes, so that’s what had me begin my search for choral music.

For all its beauty, music like this was also propagandist in 16th century England, designed to instil in people the overwhelming power of God and monarch. Sung by huge choirs in vast cathedrals, it must have been absolutely staggering to listen to. Presumably the desired effect was to leave people with a sense of awe that reinforced their religious belief, their every thought feeling more profound than it might have been before.

In a modern context, try lying in bed with your own boring thoughts with this music in your headphones and it will have the same effect, so why not steal some of that! As a soundtrack it helps to take these apparently mundane but very formative moments shared by the characters, and elevate them to almost divine status.

The very talented McKenzie Stubbert, a composer based in LA, read my treatment along with my proposal to use Thomas Tallis and was immediately onboard. He had been brought up on church music, obviously knew Tallis and understood exactly what I was getting at. I gave him a couple of sections I particularly liked and he composed the wonderful instrumental arrangement you can hear in the film.